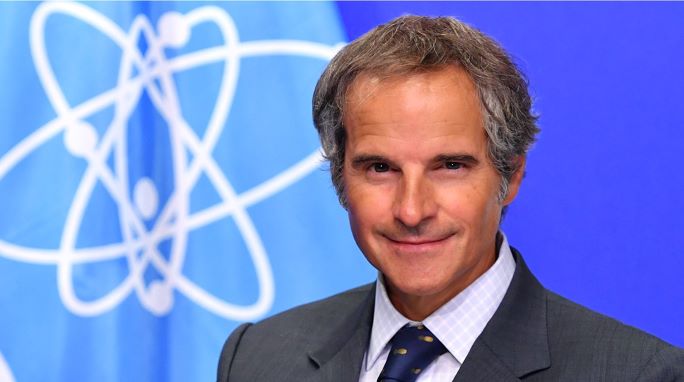

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi assumed office on December 3, 2019. Mr Grossi is a diplomat with over 35 years of experience in the field of non-proliferation and disarmament. In 2013, he was appointed Ambassador of Argentina to Austria and Argentine Representative to the IAEA and other Vienna-based international organizations. In 2019, Mr Grossi acted as President Designate of the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), and from 2014 to 2016 he served as president of the Nuclear Suppliers Group, where he was the first president to serve two successive terms. In 2015, he presided over the Diplomatic Conference of the Convention on Nuclear Safety, securing unanimous approval for the Vienna Declaration on Nuclear Safety – a milestone in international efforts in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. From 2010 to 2013, he served as Assistant Director General for Policy and Chief of Cabinet at the IAEA. Previously, he held several senior positions in the Argentine Foreign Service, including as Political Affairs Director General from 2007 to 2009. Mr Grossi was Chief of Cabinet at the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in The Hague from 2002 to 2007. (Source: IAEA)

The following is the interview given to Carlo Patti, professor from the Goiás Federal University, and to CEBRI-Journal's editors, Hussein Kalout and Feliciano de Sá Guimarães, in August 2022.

There is no doubt that 2022 brings many challenges for the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and for regimes related to nuclear energy. These challenges are related to the current international scenario (war and post-pandemic transition period) and pre-existing conditions, such as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), disarmament, Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), among others. Regarding issues prior to 2022, do you think the universalization of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) Additional Protocol to safeguard agreements is possible?

The issue of the additional protocol to the comprehensive safeguards agreements (CSAs), as envisioned in the Non-Proliferation Treaty, is a very important one. Here, I think we would need to recall the origin of this matter. In the 1990s, it became clear that the traditional CSA would not be enough to cover the whole range of nuclear activities, in particular in countries having ambitious, sophisticated, and fully diversified nuclear programs. So, the additional protocol was negotiated within the IAEA, at the IAEA Board of Governors, with the participation of all Member States. I believe it is the natural evolution of the safeguards system. It is becoming universal and it must be universal – so that every country with relevant activities will show full transparency. Transparency should not be a political bargaining chip. It should be the responsible answer of mature nuclear countries, commensurate with their nuclear activities.

Do you envision, especially with a possible change of government in Brazil, a change in Brazil’s position regarding the Additional Protocol?

When it comes to the adoption of the additional protocol and the position of respective governments, I wish to believe that countries have an approach that is not dependent on the political color of the party in government. If we were to accept the logic that “political force A” would be for the additional protocol, against the beliefs or the preferences of a different political force, then the whole foundation of that commitment on the part of the State would be fragile. I think that particularly in countries where this issue has been debated, like Brazil or Argentina, the preferred option should be a wide consensus among all political forces, with the belief that having the fullest possible coverage and endorsement of the IAEA safeguards regime is the better course of action, given that these countries have important nuclear activities. I had very constructive preliminary discussions with the authorities in Brazil and I am optimistic about the overall course of action – something that I intend to continue with the next Brazilian government, be it from whichever party, of course.

After thirty years since the establishment of the Brazilian–Argentine Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (ABACC) and twenty-eight years since the entry into force of the Quadripartite Agreement (Argentina, Brazil, ABACC and IAEA), how do you evaluate the experience of collaboration between the various parties?

The experience of ABACC has been remarkable. And I say this with pride. I belong to the generation of then-young Brazilian and Argentine diplomats who fought for full cooperation between the two nations on this key technology, which could have made us drift apart and set on a race. This would have been unthinkable and very detrimental to our cooperation and to both then-nascent democracies. ABACC requires full support from Brasília and Buenos Aires. We need to know that, as much as we are proud of our nuclear achievements and the technological prowess that both countries are showing, we need to underpin this with a truly strong inspection effort by ABACC. I believe that the “first-generation ABACC,” if I may put it this way, should be reinforced by a stronger binational agency.

What is the importance of the recent discussions between the IAEA and Brazil on the issue of inspections of the nuclear submarine? In your opinion, what is the importance of the Brazilian nuclear submarine for the international safeguards regime?

The emergence of the naval nuclear propulsion issue is undeniably one of the most significant features of the current safeguards debate. We see it in the South Atlantic, with Brazil, but we also see it in Asia, in the so-called Indo-Pacific, with AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom, and the United States Pact). We know, and I have said this publicly, that the current legal framework foresees the possibility of naval nuclear propulsion. At the same time, we cannot overlook the fact that this technology and the way it would be applied to a vessel imply that nuclear material – and a large amount of nuclear material at weapon-grade or potentially weapon-grade – could be excluded from the safeguards inspections. This is why the applicable law indicates that availing oneself of this possibility would require special arrangements with the IAEA.

We received a letter from the Brazilian government formally starting this process by indicating that Brazil would indeed like to benefit from this and would like to start negotiations. We have already had a first meeting in Vienna with the Brazilian technical and diplomatic team and my safeguards and legal inspectors. I am confident that this process will continue in a constructive way. It is a very complex matter and it requires very detailed consideration of many aspects – technological and legal, as I mentioned.

The war in Ukraine, as seen in recent months, represents a challenge for the IAEA. For the first time in history, the agency needs to guarantee nuclear safety and safeguards in a country that is involved in a conflict while at the same time hosting many nuclear plants and a sensitive area like Chernobyl. What are the main challenges that the war in Ukraine is creating for the agency's action in that country?

It is true that, in terms of nuclear activities across the world, the war in Ukraine has presented an unprecedented challenge. It is the first time that a conventional war is unfolding in the vast territory of a country that possesses a very large and complex nuclear set and range of installations. We have had a number of challenges since the war began on February 24, starting with the situation in Chernobyl. As you may remember, there were initially alarming reports about radiation levels on site. I myself led a technical mission to Chernobyl. We were able to inspect the site, to stabilize it and undertake a number of very important repairs and activities. Ever since, the situation there has returned to normal – as far as we can use the word “normal,” of course, in a country which is currently at war. The open wound, if you like, is the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant. I had the opportunity to brief the United Nations Security Council in a historic brief where, from Vienna, I presented a report on the situation and pleaded to the two countries and the international community at large to support a mission that I had prepared to lead to Zaporizhzhia. As it is widely known, there has been shelling and there have been attacks in Zaporizhzhia. While not necessarily aimed at the nuclear reactors, these attacks could endanger the external power supply and other key safety and security systems. So, it is imperative that we return to Zaporizhzhia, draw up a situational report at the plant, and undertake the necessary technical activities. At the moment this interview is being conducted, I am in negotiations with both capitals and also counting on the United Nations’ indispensable support to provide the necessary protection – with armored vehicles and the deconfliction capacities – as this place is situated at the war front. So, we are planning, and I am hoping to be there as soon as possible performing the indispensable work that the IAEA needs to do.

Regarding a possible renegotiation of the JCPOA, what are the prospects for a satisfactory solution for all parties considering the existence of an Iranian program more advanced than in 2015 and the involvement of the Russian Federation in a major conflict?

The negotiation on the revival of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – or its reinstatement after the United States’ withdrawal and the Islamic Republic of Iran’s gradual distancing from the nuclear commitments in the agreement – has been ongoing for more than a year now. This negotiation is a forum where the IAEA does not participate directly, only indirectly, because we are the guarantors and the inspectors of the agreement, so to speak. Therefore, we are in constant contact with the negotiating parties. I understand that they are very close to reaching an understanding, now dependent on matters that are not necessarily related to the nuclear chapters of the agreement. We are waiting for the results of the last exchanges. One of the issues that have been mentioned as part of a final possibility for an agreement is the clarification of some outstanding safeguards points that we have with Iran. I wish to recall that these issues are independent from the JCPOA and are to be undertaken bilaterally between the Islamic Republic of Iran and us. I am ready to engage directly with Iran as soon as possible and go to Tehran again, if necessary, to restart this process. Because I believe that in the absence of complete clarity and confirmation of what exactly the situation is in Iran, any other political agreement, including the JCPOA, would perhaps rest on quite shaky ground. So, we are actively engaged on this matter, as well.

In August 2022 the NPT review conference will finally take place. What are the main challenges for the non-proliferation regime?

The 10th Renewal Conference of the Treaty of Non-proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) finally started. I had the pleasure and the honor to open it together with the United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres, and the President of the Conference, my dear friend and colleague, Ambassador Gustavo Zlauvinen. As we speak, this process is ongoing, and some of the issues that we are covering in this conversation, of course, are also at the center of that discussion: non-proliferation; the evolution of safeguards; the situation in and around the nuclear facilities in Ukraine; the JCPOA; and other issues as well, which we should not overlook, such as those related to nuclear disarmament. Many participants, negotiators and analysts consider that a successful NPT Review Conference – if we consider “success” as the approval of a final declaration – would be very difficult to achieve. I want to believe that the NPT forms part of that solid bedrock upon which peaceful nuclear activities all over the world must be undertaken. Therefore, I have, myself, urged States parties to recommit themselves to the NPT. While I am aware of pending political and legal goals, that does not mean we should diminish our support to this absolutely fundamental success story which is the NPT.

In June 2022, the first conference of the parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons took place. What impact can this treaty effectively have on nuclear disarmament?

The issue of nuclear disarmament has certainly been on the table ever since nuclear weapons appeared, and even more after their first use in August 1945. Throughout the Cold War, negotiations have taken place to try to reduce the number of nuclear warheads, which, at the height of the Cold War, reached incredibly high – one could even say ‘absurd’ – levels. A rather positive tendency ensued whereby nuclear weapons were being reduced quite steadily, until a few years ago, when the process seemed to stall. Now, there are even indications that countries might be reversing the trend and embarking in the manufacturing of more nuclear weapons. Of course, the goal of a nuclear weapon-free world is something we have all embraced as an international community. There is no doubt about that. It is part of the NPT, and some countries decided to take an additional step by entering a new agreement – the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Until now, this has been strongly contested by the nuclear weapon States, who consider it flawed. My impression is that the process and the aspiration continue. It will persist, to find different manifestations, like the TPNW, within the NPT system and perhaps outside of it – hopefully with negotiations among the main possessors of nuclear weapons like the United States and Russia, and with the participation at the right time of others like China, the United Kingdom and France, and perhaps even others outside the NPT. What is important is to keep the commitment alive and try to remember at all times that nuclear weapons and tensions should be reduced. On the side of IAEA, we are doing our part, which is a very important one on the non-proliferation front, by ensuring and helping so that no new countries will accede to these kinds of systems of destruction.

Interview granted through written medium on August 17, 2022.

Copyright © 2022 CEBRI-Journal. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original article is properly cited.