As President Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ agenda signals a possible U.S. retreat from the very international system it helped build, other actors are eager to fill the void left by a receding superpower. This paper contends that, despite the BRICS’ acknowledged potential to serve as a catalyst for change in the international arena, their persistent lack of cohesion, divergent priorities, and conflicting foreign policy interests hinder their ability to meaningfully shape the emerging global order.

In his classic work Tout Empire Périra, the renowned French historian Jean-Baptiste Duroselle (1981) presents his bold, although controversial, theory of the rise and fall of empires. According to Duroselle, a nation's power is determined, among other variables, by the manner in which the State interacts with other actors in the international system. He contends that, since the sources of domestic power of a nation are neither permanent nor immutable, and because the nature of the interaction between actors in the international system can undergo dramatic changes, a country’s power inevitably tends to erode over time, leading to an irreversible decline.

Although from a different perspective, Paul Kennedy (1987) revived this debate in the late 1980s with his best-selling book The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, which sought to analyze and explain the causes of the relative decline of American power. While drawing attention to the growing challenges to the United States´ global leadership–in a context of declining economic performance and the geostrategic challenge posed by a rapidly growing Japan, then the world’s second-largest economy–Kennedy´s work was based on two main premises. First, history demonstrates that all great powers in the modern Westphalian international system have experienced a similar cycle: emergence, rise, apex of their power, and then relative decline. Second, this general pattern underscores that no great power has been able to maintain its dominance in perpetuity, and the U.S. would be no exception to this historical rule.

Despite the merits of these two essential reference works, neither addresses in a specific or substantive manner the potentially imminent changes in the hierarchical structure of the international system of States, emerging geostrategic disputes, new opportunities for international engagement, or the observance of international norms and regimes. The analysis of these issues is particularly relevant at a time when President Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” initiatives permeate the international agenda, create global uncertainties, and threatens to result in a voluntary self-retreat from the liberal international order which the U.S. helped to shape–an order that enabled the country, along with much of the world, to grow and prosper. Such a development could come, as some analysts argue, to potentially diminish the United States’ relative political and economic influence and lends renewed significance to the arguments advanced by Duroselle (1981) and Kennedy (1987).

In this context, other relevant actors are expected to make efforts to fill the international void left by an apparently waning superpower. China and Russia are frequently identified as countries that could benefit from American retrenchment and assert more prominent roles in global affairs. Such transformations in the international system might also come to signal a new era in which strategic groupings, such as the BRICS, are anticipated not only to wield greater influence on the global stage, but also to reshape and revitalize international institutions, rules, and regimes in order to align them with emerging power realities in an increasingly multipolar world.

This paper, therefore, aims to provide a critical analysis of the BRICS as an analytical category by examining some of its constitutive dimensions, inherent weaknesses and vulnerabilities. The main focus is on the political and economic relations among its members, within the context of contemporary debates on paradigm shifts in the global political economy. The objective is to assess whether genuine possibilities for effective intra-group multilateral cooperation exist and whether such cooperation could lead to significant changes in the global distribution of power. Alternatively, the analysis will consider whether internal tensions, structural strains, and inherent contradictions suggest that the BRICS forum is losing momentum, rendering its collective influence more a matter of conceptual wishful thinking than a truly transformative force in world affairs.

THE RELATIVE POWER OF IDEAS

Undoubtedly, acronyms can serve as highly effective marketing tools, creating memorable abbreviations for significant concepts and forging connections with positive associations, thereby endowing them with meaning, context, and value. The challenge of relying on acronyms, however, lies in the tendency that “once one catches on, it tends to lock analysts into a worldview that may soon be outdated” (Degaut 2015), which may well be the case with the BRICS.

In other words, the original rationale for the creation of the acronym was linked to the extent to which those countries could–in an era when the emergence of the so-called “rising powers” seemed to captivate the attention of the foreign-policy community–exert a significant impact on the global economy. This emphasis is understandable, given that the BRICS currently make up nearly 49% of the world's population, 39% to 41% of its gross domestic product (GDP), and 26% of global trade (MDIC 2025)[1]. Nevertheless, Almeida (2009) observes that:

(…) this aggregation of individual volume might make sense in this type of intellectual exercise, in which arithmetic seems to prevail over politics. However, it is unlikely to indicate global economic development trends, as these are caused by technological transformation and capital, scientific and strategic information flows.

Reality, however, is rarely so optimistic, and the intricacies of foreign affairs are far more complex than the rhetoric surrounding the transformation of the global political architecture might suggest. Despite the vast resources and capabilities of its members when considered individually, BRICS has, after sixteen summit meetings, made little progress in building a collective identity or establishing an institutional apparatus. With the possible exception of the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB), the group has also failed to formulate a strategic agenda, with concrete propositions and actions, or to develop a new conceptual framework for trade negotiations.

The following sections will explore some of the possible reasons why, beyond diplomatic rhetoric, BRICS has not yet proven to be a particularly effective collective instrument for pursuing common foreign policy objectives that would enable its members to induce a genuine global power shift or to benefit more substantially and collectively from shifting global power dynamics and eventual paradigm changes.

WHAT COULD BE DERAILING THE BRICS?

Several factors have hindered the BRICS from constructing a more compelling narrative about their role in reshaping global economy and politics. Most analysts have focused their criticisms almost exclusively on economic aspects, evaluating the association primarily by its members’ economic growth (or the lack thereof). The prevailing argument is that the initial hype and euphoria that accompanied the group–driven by their then-stratospheric growth rates–are no longer warranted. This shift is attributed to a combination of evolving global circumstances, such as the end of the commodity super-cycle, and domestic challenges faced by individual member States.

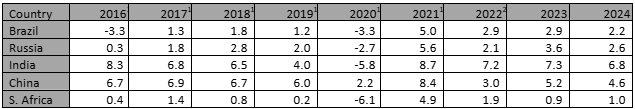

In recent years, GDP growth in Brazil, Russia, and South Africa has remained modest and volatile, as highlighted in Table 1. Although these countries exited the recessions of the mid-2010s, they have since encountered ongoing structural challenges and external shocks that continue to limit their growth potential. China, while maintaining comparatively strong growth by global standards, has recorded its lowest rates in decades as it undertakes complex structural reforms to transition its economy from investment–and export-led expansion–to a model based more on domestic consumption and innovation.

India, meanwhile, has consolidated its position as the world’s fastest-growing major economy, with annual growth consistently above 7% since 2021. However, despite these robust figures, India still grapples with persistent poverty and inequality, and rapid GDP expansion alone has not fully translated into widespread and inclusive development (World Bank 2022). Significant regional and rural-urban disparities persist. Poverty rates remain substantially higher in India’s central and northeastern States, and rural areas account for roughly 65% of those still living in poverty. Multiple dimensions of deprivation continue to affect large segments of the population (UNDP 2023). Recent editions of the Global Hunger Index and the National Family Health Survey indicate high rates of child and maternal malnutrition, inadequate sanitation, and unequal access to education and healthcare services (2023).

Overall, with four out of the five original BRICS members experiencing slow or only moderate growth, there is scant evidence at present to support the idea that the BRICS bloc is emerging as the new engine of global growth. The varied performances of its members, combined with limited economic integration and differing structural realities, underscore the challenges the group faces in sustaining collective momentum and asserting a transformative role in the world economy.

Table 1. BRICS Growth Rate in percent, 2016-2024. Source: World Bank GDP Growth (annual %) (World Bank 2025).

A decade-old paper observes that “in the global race for economic success, GDP has come to count more than any other factor, which explains why analysts believe that, by sustaining high rates of GDP growth, the BRICS are likely to generate a fundamental power shift in global governance institutions” (Fioramonti 2014, 3). However, evaluating the BRICS' success solely or primarily through GDP growth rates is not only reductive but also misleading. Similarly, assessing the group´s potential based on seemingly shared traits–such as varying degrees of corruption, high rates of illiteracy and poverty, regional and economic inequalities, overreliance on commodities, dependence on foreign direct investment, institutional weaknesses, vulnerability to asset bubbles, poor institutional and regulatory quality, and a relatively limited integration with the global economy–can also lead to erroneous conclusions. These characteristics are common to many developing countries and cannot be considered defining features of the BRICS, nor reliable indicators of the group’s capacities or future prospects.

Considering that the BRICS seek to be recognized as a platform for dialogue and cooperation among its members–not only in economic, financial and development matters but also in the political sphere–, the group´s main challenge arguably lies in the fact that each country possesses a distinctly different strategic culture. This is far from a trivial issue, as the foreign policy goals pursued by a State, which reflect its identity, interests and priorities, are largely defined by its strategic culture. For the purpose of this study, and at the risk of oversimplifying a complex subject, strategic culture can be understood as a deeply rooted cultural inclination toward particular patterns of strategic behavior or thinking. In this regard, the United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) defines it as the combination of “internal and external influences and experiences–geographic, historical, cultural, economic, political, and military–that shape and influence the way a country understands its relationship to the rest of the world, and how a State will behave in the international community” (Bitencourt & Vaz 2009, 1).

This concept highlights the idea that strategic culture is shaped by a nation’s historical experience. Since these experiences differ across States, “different States have different predominant strategic preferences that are rooted in the early or formative experiences of the State, and are influenced to some degree by the philosophical, political, cultural and cognitive characteristics of the State and its elites” (Johnston 1995, 34). The approach helps explain “what constrains actors from taking certain strategic decisions, seeks to explore causal explanations for regular patterns of State behavior, and attempts to generate generalizations from its conclusions” (Degaut 2017, 274).

Therefore, what is advanced here is that, largely due to their differing strategic cultures, the BRICS countries possess markedly distinct worldviews, foreign policy priorities and interests, diplomatic practices and preferences, as well as models and instruments of international engagement. As a result, although they periodically convene to coordinate their positions, they have thus far been unable to overcome these differences and establish a political community united by a common agenda. Furthermore, their diverse–and often divergent–interests have prevented them from reaching a common denominator on crucial issues such as climate change, human rights and humanitarian intervention, conflicts in the Middle East, terrorism, and international trade.

Despite repeated affirmations of solidarity and shared objectives on the world stage, the BRICS grouping continues to demonstrate significant divergences on major issues of international politics and security. While the bloc markets itself as a platform for dialogue, cooperation, and the defense of multipolarity, the reality is that each member’s unique historical experiences, strategic cultures, and national interests frequently lead to sharply contrasting diplomatic actions and policy stances.

As an illustrative example, while Brazil, India and South Africa have sought to promote a progressive agenda on human rights issues, China and Russia have consistently opposed such initiatives (Laskaris & Kreutz 2015). Similarly, and reflecting their historical traditions, Brazil and India have emphasized the importance of respecting sovereignty and ensuring the territorial integrity of regions in conflict–positions that led both countries to abstain from the 2011 United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolution authorizing the use of force against Libya’s Muammar al-Qaddafi. Brazil, India, and South Africa have also taken a cautious approach toward the civil war in Syria, in stark contrast to Russia’s active involvement in the conflict, which “generates new tensions for the coalition’s discourse of sovereignty” (Abdenur 2016, 111).

More recently, this divergence was strikingly evident in the aftermath of the October 2023 Hamas attacks on Israel. Brazil, then presiding over the United Nations Security Council, swiftly condemned the terror attacks against Israeli civilians and expressed support for Israel’s right to self-defense, while simultaneously calling for restraint and humanitarian protections in Gaza. Shortly afterwards, Brazil became actively engaged in multilateral organizations to demand humanitarian corridors and a ceasefire in Gaza, and harshly criticized the Israeli government, accusing it of committing crimes against humanity. Russia, on the other hand, adopted a more equivocal position, lamenting civilian casualties on both sides and calling for renewed dialogue, but carefully avoided outright condemnation of Hamas–reflecting both its regional ties and skepticism toward U.S.-led mediation.

India’s response was also distinct: it explicitly condemned the Hamas attacks and voiced solidarity with Israel, cementing the deepening partnership between the two nations. Nonetheless, India soon urged the protection of Palestinian civilians, highlighting its ongoing attempt to balance relations with both Israel and the broader Arab world. China maintained its traditional posture of neutrality, calling for an immediate ceasefire and the revival of peace talks, but stopped short of naming or condemning Hamas directly. South Africa, meanwhile, issued harsh criticism of Israel’s military response and openly compared the plight of Palestinians to its own history of apartheid, reaffirming long-standing moral and political solidarity with the Palestinian cause.

These differences are not limited to the Middle East. The war in Ukraine serves as another clear example. Russia, as a central party to the conflict, rejected any condemnation or calls for accountability. The other BRICS members refrained from opposing Russia directly; instead, they have called for dialogue and diplomacy while opposing Western sanctions and maintaining, or even expanding, economic ties with Moscow. However, their statements vary in tone and emphasis: Brazil and South Africa have occasionally expressed critiques in multilateral forums, whereas China and India have remained largely neutral, emphasizing sovereignty and non-interference.

Similar patterns appear in other domains, such as climate negotiations and reforms to global governance institutions like the UNSC. While the BRICS countries frequently advocate for greater recognition of developing nations’ interests and a more equitable international order, they seldom align on concrete reform proposals or collective action. Disagreements on climate commitments, approaches to humanitarian crises, and the question of permanent seats for Brazil and India on the Security Council further illustrate the group’s internal fragmentation.

In that particular regard, the BRICS foreign ministers’ meeting in Rio de Janeiro in April 2025 highlighted not only the group’s enduring difficulties in achieving consensus, but also how its expansion has deepened internal divisions. These challenges became particularly evident in debates over the UNSC reform. Although Brazil once again pressed its claims for a permanent seat, both China and Russia refrained from endorsing a joint declaration in support of Brazil’s bid, preferring to avoid any explicit commitment that might alter the current balance of power within the UN. Furthermore, some of the bloc’s newer African members, such as Egypt and Ethiopia, voiced objections to similar ambitions from South Africa, arguing that no single African country should be singled out as the continent’s representative on the Security Council.

These disagreements made clear that the group’s enlarged membership–bringing in new regional rivalries and competing leadership aspirations–has exacerbated preexisting difficulties in forging common positions. The reluctance of major members to support Brazil or South Africa’s individual ambitions signaled the persistence of national interests and intra-group competition, which now extend to multiple continents. As the BRICS continues to advocate for a more representative and multipolar international order, its inability to unify around two of its own members’ Security Council aspirations sharply illustrates the bloc’s structural limitations and raises doubts about its effectiveness as a coherent force in global governance.

In the same vein, initial discussions aimed at establishing a BRICS Defense Council–a forum envisioned as the cornerstone of a future military alliance–have revealed a certain level of disagreement among member countries on security and defense matters. The idea of such a military forum has been advocated almost exclusively by Russia, which sees it as a means to counterbalance North-American influence within the UN system and, in particular, to respond to NATO's expansion and operations. Chinese policymakers have not dismissed the initiative, viewing it as potentially fitting within the broader framework of the strategic competition with the United States. However, they are still evaluating to what extent the creation of a defense council could undermine China’s well-established position in the UNSC and its ambitions for a more prominent role within the UN system.

India and South Africa, on the other hand, seem to entirely dismiss the idea, each for a variety of reasons. First, an element of regional rivalry cannot be disregarded (Cooper & Farouk 2016). India and China are increasingly at odds over several critical issues, including terrorism, Beijing’s aspirations in the South China Sea, and competition for influence in countries such as Cambodia, Nepal, Myanmar and neighboring regions. Additionally, New Delhi’s efforts to strengthen its regional position through closer ties with the U.S. and Japan have further heightened tensions.

Particularly concerning for New Delhi is China's strategic alliance with Pakistan. This ongoing geopolitical rivalry has led Beijing to refrain from officially endorsing India’s bid for a UNSC seat. In response, India has persistently blocked China’s admission to the IBSA initiative, a political consultation forum consisting of India, Brazil and South Africa, on the grounds that it is a coalition of democratic countries–a position that has, so far, aligned with Brazil’s own stance.

Russia follows the same line of reasoning; however, although it officially advocates for the reform and expansion of the UNSC, it does so because of the low diplomatic cost, as it does not regard any real possibilities for reform in the short or medium term. Russia believes such an expansion would have undesirable consequences for its strategic freedom of action, especially in the “Near Abroad”–a Russian foreign policy cornerstone used to refer to the geostrategic space encompassing the former Soviet republics in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe.

South Africa, for its part, does not seem to be expanding the role or size of its armed forces to assert itself as a regional power through rearmament–unlike other BRICS countries. Consequently, it appears to reject the idea of a Defense Council, arguing that such an initiative would likely be both futile and counterproductive, serving only to undermine international law. Brazil, in turn, neither explicitly supports nor opposes the proposal, as the country has not yet determined which benefits it would gain from that forum.

Certainly, a degree of cooperation in military and security affairs is both possible and already occurring–particularly in areas such as cybersecurity and information exchange. However, three factors significantly reduce the likelihood of the establishment of a formal defense council, security forum, or military alliance in the near future.

First, the five BRICS countries exhibit substantial divergences in their defense and security interests, resulting in most cooperation occurring on a bilateral rather than multilateral basis. Second, the members remain ambivalent about how to reconcile their respective regional priorities and commitments with their participation in the BRICS framework. Lastly, diplomatic rhetoric notwithstanding, there is no clearly identifiable threat capable of uniting the five powers around a common security agenda, apart from the aim of counterbalancing the so-called “Western hegemony”–a term increasingly ill-defined and arguably losing practical significance as the international system becomes progressively more multipolar.

In summary, although the BRICS present a common front rhetorically, the group has consistently struggled to articulate a unified position on the world’s most pressing security and diplomatic challenges. The diverging attitudes of its members on crucial issues reflect the enduring primacy of national interests and strategic cultures within each country, ultimately limiting the bloc’s effectiveness and influence as a cohesive actor in international affairs.

THE BRICS AND THE AMERICAN LEADERSHIP

For generations, the United States has largely set the terms for the global order, shaping it to reflect its own interests, norms and values. Now, at a time when the U.S. appears to be turning inward, and President Trump's “Make America Great Again" foreign policy seems to be redefining the very concept of national interest–with the underlying premise that international relations are a zero-sum game–, questions have arisen about who would possess the attributes necessary to potentially fill the power vacuum that could emerge if the U.S. were to abdicate its role as a global leader.

Some analysts (Löfflmann 2019) argue that, to some extent, Trump’s first-term foreign policy represented a continuation of Barack Obama’s “leading from behind” philosophy, as both administrations favored a broad strategic shift toward global restraint–a move that effectively amounted to a virtual abdication of global leadership. This approach, for instance, was actively exploited by Russia and Iran to expand their influence in the Middle East and assert their leadership in the Syrian crisis, to the detriment of American interests and influence.

Likewise, in one of the first formal initiatives of his first term, President Trump withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a project originally launched under the George W. Bush administration to establish high-standard trade rules with Asia-Pacific countries, and widely praised as the largest multilateral trade agreement to date. Beyond its economic significance, the TPP was also intended to counter China’s growing economic influence in the region–a measure that formed a key part of the United States’ high-profile “pivot to Asia” strategy.

However, Trump’s efforts to overhaul the global regulatory mechanisms traditionally championed by the U.S. may have backfired. The U.S. withdrawal from the TPP ultimately paved the way for the establishment of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and the ten member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This trade agreement encompasses around 30% of global gross domestic product, trade volume, and population[2].

China, the most powerful BRICS member, wasted no time in taking advantage of the apparent American retreat to lay the foundations for what they expected to become a new era of globalization. Through the launch of its ambitious “Belt and Road” initiative–an estimated US$ 1 trillion development project–China seeks to expand its influence by boosting trade, providing substantial funding for infrastructure development, and stimulating economic growth primarily, but not exclusively, along the centuries-old Silk Road routes. The Chinese initiative, which enjoys the support of both Brazil and Russia, recognizes no geographic boundaries, reaching as far as Latin America.

None of these initiatives, however, can obscure the fact that the United States remains an indispensable nation for the stability of the international order. Its economic, military or political capabilities have not declined significantly in qualitative terms, although a reduction in its relative power and primacy in global politics is certainly noticeable. Nevertheless, the triumphalism that characterized U.S. foreign policy discourse since the earliest phases of globalization seems to have faded. Combined with the persistent slowdown of economic growth in the U.S., this may have eroded America's “will to power”.

More than merely affecting U.S. domestic politics, the measures adopted by Trump in his second term in office have marked a turning point in international politics, prompting a reassessment of the premises and structures that have underpinned the global architecture for decades. This movement, although not yet amounting to the gestation of a nascent New World Order, goes far beyond a simple shift in priorities: it represents a strategic reorientation aimed at redefining the role and the mode of engagement of the U.S. in the world.

The new guidelines of American foreign policy, founded on the resolute defense of national interests and grounded in a “realist perspective of international relations”, appear to be anchored in several pillars the proper understanding of which is essential to decode the scope and meaning of the measures being implemented.

President Trump believes that the U.S. is experiencing a sharp decline as a result of its behavior on the global stage, particularly its commitment to alliances, and that the American-led liberal international order has failed its own people. He is urging other countries to shoulder a greater share of the burden–doing more and paying more–which is why he is redirecting his agenda toward domestic politics and a narrower set of national interests.

The first pillar–pertaining to the economic and commercial dimension–seeks to promote an agenda that redefines U.S. interests, based on reducing the country’s direct involvement in multilateral issues and platforms, and on a clear preference for bilateral negotiations as the central axis of political action.

From this perspective, by favoring the individual viewpoint of "fair and reciprocal trade" and sidelining the World Trade Organization (WTO)–already heavily criticized for its inertia and sluggishness–Trump questions the legitimacy and efficiency of the international trade system, unilaterally imposing tariff barriers and retaliatory measures, and reevaluating trade agreements, such as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), successor to NAFTA.

Although these measures are grounded in encouraging domestic production ("US Shoring"), job creation, and increases in income and internal revenue through consumption growth, they have the potential–as yet untested–not only to distort global supply chains and trigger inflationary surges, but also to cause instability and uncertainty in global financial markets and to accentuate trends toward deglobalization, in a scenario where centrifugal forces of fragmentation are gaining momentum.

President Trump’s decision to adopt tougher, protectionist trade policies–by imposing steep tariffs on imported goods from several key trading partners–has prompted threats of retaliation and heightened fears of a full-blown trade war. Some of Trump’s measures could ultimately trigger a domino effect leading to global imbalances in the long term by restraining exports, discouraging investment, and undermining business and consumer confidence. In the short term, however, their primary unintended consequence may be to call into question and undermine the very foundations of the liberal order, as well as to push a weakened Europe and Latin America closer to China. Nobel laureate economists, such as Paul Krugman and Jeffrey Sachs (Mannweiler 2025), observe that rather than “Make America Great Again,” such policies could further contribute to shifting the global economic and strategic center of gravity to the Indo-Pacific region and accelerate the process of making China great again.

These circumstances lend renewed momentum to initiatives aimed at fostering greater multipolarity in the world, in a context where strategic groupings such as the BRICS are expected to gain greater prominence. In fact, at the outset, the steady rise of the BRICS to such a preeminent position appeared to be an almost irreversible trend. In light of current economic downturns and diplomatic disagreements within the group, however, the evidence suggests that narratives about this inexorable ascent may be overstated.

Although the shifting of global power may not be taking place as quickly as assumed, the current transition will likely prompt the main actors in the global stage to recalibrate their foreign policies and rebuild bilateral and multilateral ties, so as to pursue the stability of the international system and settle down into a pattern of relationships more adequate to a multipolar world.

As the U.S. turns inward, Beijing appears to be acutely aware of the opportunity to reshape the international system according to its own interests, in a scenario where the BRICS platform can serve as an effective instrument for its objectives. China values the BRICS for three main reasons: (i) as a geopolitical cover to disguise its unilateral actions, which usually entail higher costs and risks; (ii) as an instrument to counterbalance U.S. power, but within a framework of collective action, supposedly contributing to improved global governance; (iii) as a mechanism to monitor the strategic actions of its regional rivals, Russia and India, while simultaneously advancing its own unilateral interests with the other bloc members (with greater ambitions in less developed countries in South Asia and Africa) and in other regions, particularly in economic and commercial spheres.

In this regard, the BRICS expansion process does not contribute to deepening the group’s internal cohesiveness, but it is clearly a step forward in expanding China’s geopolitical clout. By emphasizing apparent multilateralism and operating within the framework of a collective action mechanism, Beijing can use the BRICS to mitigate perceptions that it is fundamentally seeking to challenge the international status quo, while quietly carving out a greater global role for itself in a new order it aims to build–one that is perhaps not entirely grounded in the same liberal values, principles, and practices to which the world has become accustomed over the past seventy years.

In this scenario, the BRICS–dismissed by the Obama, Biden and Trump administrations as a dysfunctional political arrangement–should not be entirely discounted, as it could still come to play a leading role in the global economy and strategic landscape, despite its structural imbalances. Intragroup cooperation can offer each member an important platform to leverage its collective influence for individual advancement. By acting together, however, the association as a whole can make a meaningful difference in world politics and global governance, particularly on issues directly related to the immediate interests of developing countries. From this perspective, the apparent contrast between the potential rise of the BRICS and U.S. protectionist policies should not be viewed through the narrow lens of a false dichotomy, but rather as a development capable of initiating a shift in the international debate and providing a more accurate picture of the global distribution of power.

CONCLUSIONS

Certainly, there are numerous misperceptions and misconceptions about the BRICS and its role. Perhaps the clearest way to define the association is by clarifying what it is not and why it cannot offer more than it currently provides. BRICS is not an economic or trade bloc. It is not a process of deep integration. It is not an alliance in the classical sense of the term. Rather, BRICS is a platform for cooperation–one that, through both mistakes and successes, is striving to reinvent itself and pursue innovative paths in order to create an international environment more conducive to advancing the interests of its member countries. Apart from China, the group does not seek to fundamentally overturn the global order; rather, it aspires to secure a better seat at the table while striving to make that table more inclusive.

There is no doubt that, individually, the BRICS countries have been gaining weight and importance in global affairs and can no longer be ignored by any measure. Collectively, the association has the potential to serve as an important political partnership and diplomatic tool. Initiatives adopted so far, however, remain limited in their depth, scope, and acceptance, reflecting the group’s relative lack of cohesion, differences in priorities, economic models, and foreign policy interests. When viewed within a broader framework, these variables manifest as difficulties for the group in forging consensus around a platform of collective action–and, consequently, in shaping the international agenda.

As ideas require coordinated and continuous effort to be translated into reality, the BRICS must reconcile rhetoric and action–and capitalize on any potential American retreat–by realigning their prospects for cooperation, an endeavor that hinges on four main elements: first, there must be the political will to make the mechanism a true priority; second, there must be the capacity and willingness to overcome and reconcile diverging interests and ambitions; third, the group must be able to withstand the political and economic costs of countering U.S. power; finally, effective initiatives must be adopted to deepen cooperation and develop strategic intra-group relationships.

Without taking these elements into account, BRICS will hardly be able to realize its full potential and will continue to be portrayed as a heterogeneous association of competing powers–a mere bargaining coalition, an alliance of convenience with an “anti-Western” agenda–rather than what could be seen as the possible engine of a global power shift in the future. More importantly, unless the asymmetry of power within the group is addressed, the other BRICS countries may ultimately find themselves relegated to the role of junior partners in the construction of a new, China-led world order–if not simply serving as pawns in a larger global geopolitical game.

Notas

[1]As of January 6, 2025, BRICS has 10 full members: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and United Arab Emirates. Joining them are eight partner countries that are on the path to full membership: Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Thailand, Uganda, Uzbekistan

[2]The RCEP was conceived at the 2011 ASEAN Summit in Bali, Indonesia, while negotiations formally launched during the 2012 ASEAN Summit in Cambodia. The treaty was formally signed on November 15, 2020 at the virtual ASEAN Summit hosted by Vietnam. For the first ten ratifying countries, the trade pact took effect on January 1st, 2022.

References

Abdenur, Adriana. 2016. “Rising Powers and International Security: The BRICS and the Syrian conflict.” Rising Powers Quarterly, 1(1): 109-133. https://rpquarterly.kureselcalismalar.com/quarterly/rising-powers-and-international-security-the-brics-and-the-syrian-conflict/.

Almeida, Paulo Roberto de. 2009. Trade and International Relations for Journalists. Rio de Janeiro: Cebri-Icone.

Bitencourt, Luis, & Alcides C. Vaz. 2009. "Brazilian Strategic Culture." Finding Reports 5, Florida International University.

Brütsch, Christian & Mihaela Papa. 2013. “Deconstructing the BRICS: Bargaining Coalition, Imagined Community or Geopolitical Fad?” Chinese Journal of International Politics, 6(3): 299-327. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/pot009.

Degaut, Marcos. 2017. “Brazil’s Military Modernization: Is a New Strategic Culture Emerging?” Rising Powers Quarterly, Vol. 2(1): 271-297. https://rpquarterly.kureselcalismalar.com/quarterly/brazils-military-modernization-new-strategic-culture-emerging/.

Degaut, Marcos. 2015. “Do the BRICS Still Matter?” A Report of the CSIS Americas Program, October 21, 2015. https://www.csis.org/analysis/do-brics-still-matter.

Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste. 1981. Tout empire périra – Une vision théorique des relations internationales. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne.

Fioramonti, Lorenzo. 2014. “The BRICS of Collapse? Why Emerging Economies Need a Different Development Model.” OpenDemocracy, February 26, 2014. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/brics-of-collapse-why-emerging-economies-need-different-development-model/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

GHI. 2023. Global Hunger Index. https://www.globalhungerindex.org/pdf/en/2023.pdf.

Johnston, Alastair Iain. 1995. “Thinking about Strategic Culture.” International Security, 19(4): 32-64. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539119.

Kennedy, Paul. 1987. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Vintage Books.

Laskaris, Stamatis & Joakim Kreutz. 2015. “Rising Powers and the Responsibility to Protect: Will the Norm Survive in the Age of BRICS?” Global Affairs, 1(2): 149-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2015.1032174.

Löfflmann, G. 2020. “From the Obama Doctrine to America First: the Erosion of the Washington Consensus on Grand Strategy.” International Politics, 57: 588–605. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-019-00172-0.

Mannweiler, Laura. 2025. “‘Monstrously Destructive’ and ‘Unwise’: Leading Economists React to Trump’s Tariffs.” USNews, April 3, 2025. https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2025-04-03/monstrously-destructive-and-unwise-economists-react-to-trumps-tariffs.

Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio do Brasil. 2025. BRICS Brasil 2025.

O’Neill, Jim. 2001. “Building Better Global Economic BRICs.” Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper 66, 30 de novembro de 2001. https://www.almendron.com/tribuna/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/build-better-brics.pdf.

UNDP. 2023. 2023 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). Human Development Report. https://hdr.undp.org/content/2023-global-multidimensional-poverty-index-mpi.

World Bank. 2022. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2022: Correcting Course.

World Bank. 2025. "GDP Growth (annual %)." World Bank Group. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG.

Submitted: May 14, 2025

Accepted for publication: June 6, 2025

Copyright © 2025 CEBRI-Journal. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original article is properly cited.