This article assesses whether, after the hiatus of Temer and Bolsonaro, Lula continued to pursue an overstretched foreign policy in his third term. We conclude that although he has restrained from those impulses, this is less due to any learning from past mistakes and primarily because of the pressures of the new geopolitical order. To make these points, we leverage data and analytical techniques to measure the overstretch along the lines of the project Foreign Policy in Numbers, hosted at the International Relations Institute of the São Paulo University.

Since taking office in 2003, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has profoundly impacted Brazilian foreign policy. His approach, characterized by a focus on both regional and global influence, was deemed a clear example of foreign policy overstretch. This term typically refers to a State's ambition to project influence beyond its capacity, potentially leading to overextension and diminishing returns. As Lula enters the third year of his third term, assessing whether he continues to pursue an overstretched foreign policy, or it has recoiled–due to learning or the pressure of a new geopolitical order–requires consideration of both his speech and actions. A comprehensive analysis of such dynamics requires leveraging big data and new analytical techniques. Here, we give a glimpse of how such an analysis of foreign policy overstretch could be analyzed and point to the potential of projects such as Foreign Policy in Numbers[1], hosted at the International Relations Institute of the University of São Paulo, which can contribute to policy evaluations.

LULA'S FOREIGN POLICY IN CONTEXT

Efforts to enhance the Brazilian role on the global stage marked Lula's initial two terms. His administration sought to bolster relationships with developing countries, mainly through platforms such as the BRICS (Sotero & Armijo 2007). Lula emphasized South-South cooperation and aimed to reposition Brazil as a leader among emerging economies. This ambitious agenda, however, led to criticism of overstretching, as the government was perceived to be pursuing aspirations without sufficient domestic support or capacity.

[...]Brazil played pivotal roles in discussions related to the Doha Round of trade negotiations and global climate agreements, seeking to balance national interests with a commitment to global citizenship.

Particularly notable was Lula's involvement in negotiations around international trade, climate change, and nuclear proliferation. During his Presidency, Brazil played pivotal roles in discussions related to the Doha Round of trade negotiations and global climate agreements, seeking to balance national interests with a commitment to global citizenship. Despite these efforts, critics pointed out that such extensive commitments strained Brazil's resources and diverted attention from pressing domestic issues. A crucial case of overstretch took place in 2010 when Brazil and Turkey sought to mediate a nuclear agreement with Iran to address concerns over its nuclear program. Their efforts culminated in the Tehran Declaration in May 2010, which aimed to facilitate trust-building measures. However, the agreement was turned down in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) by 12 votes to two, with all five permanent members voting against the initiative.

Overstretch became all too evident after 2013, during President Dilma’s administration, when Brazil's economic slowdown resulted in reduced credit for global investments and budget cuts to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Embassies struggled to cover basic expenses, diplomats faced delays in receiving allowances, and the country's debts to international organizations nearly led to suspensions. These issues exposed the unrealistic nature of Brazil's prior ambitions, prompting a continued retreat in its foreign policy. In a major debate in the pages of the Argentine newspaper La Nacion, Schenoni (2017) argued this point forcefully, but a former secretary-general of Itamaraty and Brazilian Ambassador to Argentina at the time, Sérgio França Danese, opposed Schenoni's argument. Danese (2017) claimed that "Brazil represents the eighth-largest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the world, not to mention other facts, such as being the fifth-largest country in population and territory, and the main biodiversity reserve on the planet. [...] In each of these areas, Brazil possesses assets—natural, economic, human, and diplomatic—that grant it a place at the table of global negotiations." In other words, according to Danese, it was not enough to show that Brazil expanded. One must consider what would have happened to a Brazil-like country without a PT government to argue convincingly for overstretch. Did Lula drive this overexpansion, or was it simply the foreign policy growth that any country like Brazil would have undergone in that historical context?

Schenoni et al. (2022) addressed this by employing statistical techniques suitable to generate such counterfactuals, demonstrating that a hypothetical Brazil without Lula would not have stretched beyond its capacity, even in the same context of a Chinese-led international economy. Overextension was empirically traceable in indicators such as the number of embassies, participation in peacekeeping organizations, participation in international organizations, and South-South foreign development aid. Overstretch was indisputable, but questions remained: Why did it happen? And could it happen again?

THIRD TERM: NEW CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

As Lula resumed the Presidency in 2023, the international landscape had changed significantly. The geopolitical tensions arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, the ongoing impacts of climate change, and the rise of new economic powers present both challenges and opportunities for Brazilian foreign policy. We scrutinize Lula's current foreign policy through the lens of whether it reflects a continuity of the ambitions of yore or a more refined, strategic approach.

Lula's early actions in his third term indicate a desire to regain Brazil's position as a global leader, particularly in climate policy. He has reopened dialogues with nations that were strained under his predecessor and pledged to reduce deforestation in the Amazon, recognizing the global implications of environmental degradation. Already in 2023, for example, Norway, Germany, Switzerland, the United States, the United Kingdom, Denmark, the European Union and Japan made disbursements to the Amazon Fund managed by BNDES, ending the year with R$ 3.5 billion. This move could signify a tactical reassessment where Lula aligns Brazil's foreign policy with global priorities and domestic capabilities rather than indiscriminately pursuing a broad-spectrum influence.

Although Lula offered himself to mediate in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, in what seemed a revival of overstretch, the warring parties did not accept it–and Brazil ended up paying more costs or reaping more sympathy out of an alleged bias towards Russia. While Brazil was the only BRICS country to vote in favor of the United Nations (UN) resolution condemning the Russian invasion and calling for the withdrawal of Moscow's troops from Ukrainian soil, Lula rejected the request from the U.S. and Germany to send ammunition to Kyiv and criticized North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for supporting Ukraine and prolonging the war. Ukraine translated this posture as an alliance between Brazil and the aggressor Russia for commercial reasons. In 2023, President Lula suggested that Kyiv recognize Russian sovereignty in Crimea to achieve peace, a declaration interpreted as support for Moscow. Brazil's neutrality in the conflict oscillates between maintaining ties with Russia and China, pleasing the U.S. and the European Union, and still trying to maintain what remains of coherence in respecting the principle of non-intervention and respect for sovereignty.

[Brazil's neutrality in the [Russia-Ukraine] conflict oscillates between maintaining ties with Russia and China, pleasing the U.S. and the European Union, and still trying to maintain what remains of coherence in respecting the principle of non-intervention and respect for sovereignty.

Likewise, Lula sought to get the least involved in the Venezuelan democratic crisis that peaked in 2024, neither corralling President Maduro nor backing the triumphant, but repressed, opposition. The Brazilian government expected to convince Maduro to respect the fairness of the electoral process, a fact agreed in Barbados in 2023, together with the United States. The exchange of fair elections for lifting U.S. sanctions did not work, and Brazil's hesitation jeopardized its possible leadership in the region. Although Brasilia acted to veto Venezuela's entry into BRICS at the end of 2024, a clear sign of retaliation, the failure to persuade Maduro highlights Brazil's low capacity to command the stability of the countries around it. Regional instability can restrict Brazil's extra-regional projection, limiting the extent of its influence and power in the global arena (Mariano & Ramanzini 2023). It might also undermine his budgetary negotiations with the Brazilian armed forces, who have created a new mechanized cavalry regiment in Roraima to stop Venezuelan ambitions in the Essequibo region of Guyana and are becoming an increasingly influential actor in domestic politics.

In the agendas revised above, the record is mixed. They paint the picture of a Lula who is trapped in his former rhetoric and cannot escape his former role but is, at the same time, much more constrained by the lack of a favorable international environment. So, a reader might ask, did overstretch occur or not? The devil is in the metrics.

OVERSTRETCH REVISITED? NOT IN SIMILAR INDICATORS (BUT MAYBE ELSEWHERE)

The perception of a multipolar world, combined with a favorable international economy, drove the expansion of Brazilian foreign policy during the first 8 years of Lula's administration. The commitment of national resources to the expansion of Brazilian influence reached the economic, diplomatic and security dimensions, strengthening the legitimacy of Brazil's demand for reform of the post-Cold War global order. In the economic sphere, the expansion of national companies has become a central focus of the foreign policy agenda, interpreted as essential for domestic socioeconomic development (Ricupero & Barreto 2007).

The commitment of national resources to the expansion of Brazilian influence reached the economic, diplomatic and security dimensions, strengthening the legitimacy of Brazil's demand for reform of the post-Cold War global order.

Until the beginning of the 21st century, the internationalization of Brazilian capital was considered low in relation to other emerging economies (Iglesias & Motta Veiga 2002; Tavares 2006), a scenario abruptly reversed during Lula's first two terms in office. The Brazilian foreign direct investment totaled US$ 1 billion per year until 2003, averaged US$ 14 billion per year from 2004 to 2007 and reached an impressive US$ 56 billion in 2007 alone (Saggioro 2012, 62). The degree of internationalization of Brazilian companies quickly approached that of China and India, two major emerging economies.

The National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) loans for financing international services played an important role in this expansion. Between 2001 and 2010, the amount of credit granted by BNDES to these companies rose from US$ 194 million to US$ 1.3 billion, approximately fifteen times the growth rate of the country's economy in the same period. The countries that received the most BNDES loans in this modality during the period were Angola and Venezuela, closely followed by Argentina and Mozambique, in line with the government's political aspirations to lead the region and expand Brazil's global influence, with special attention to the African continent. The global expansion of Brazilian public and private companies was also facilitated by presidential diplomacy (Malamud 2005). Between 2003 and 2010, President Lula visited an average of thirty countries per year, more than double the thirteen countries of his predecessor, often accompanied by Brazilian entrepreneurs (Cason & Power 2009; Burges & Bastos 2017). The phenomenon was an important pillar of the overstretching of Brazilian foreign policy, given the low sustainability of this model of international economic insertion, which terminated in 2015 with the end of BNDES loans.

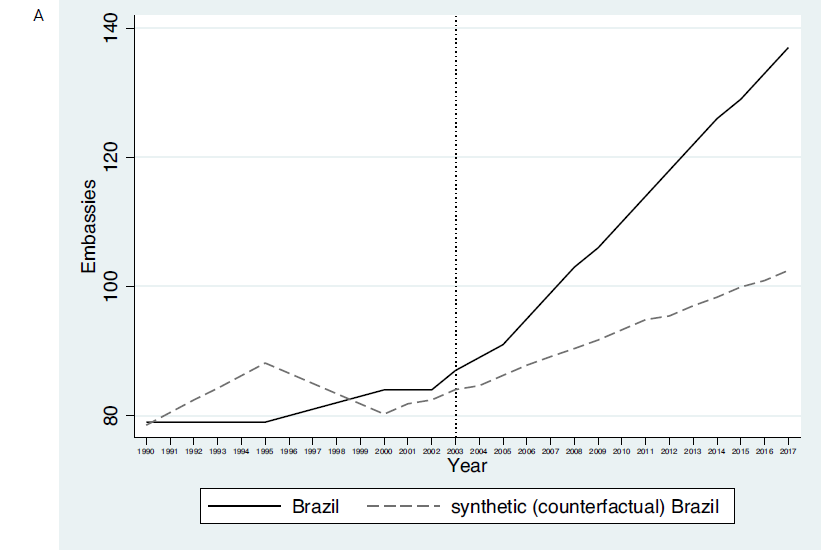

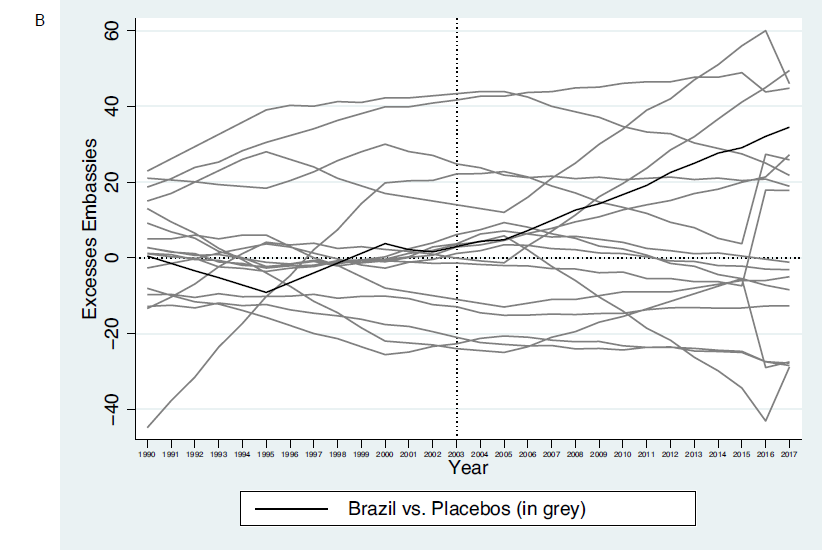

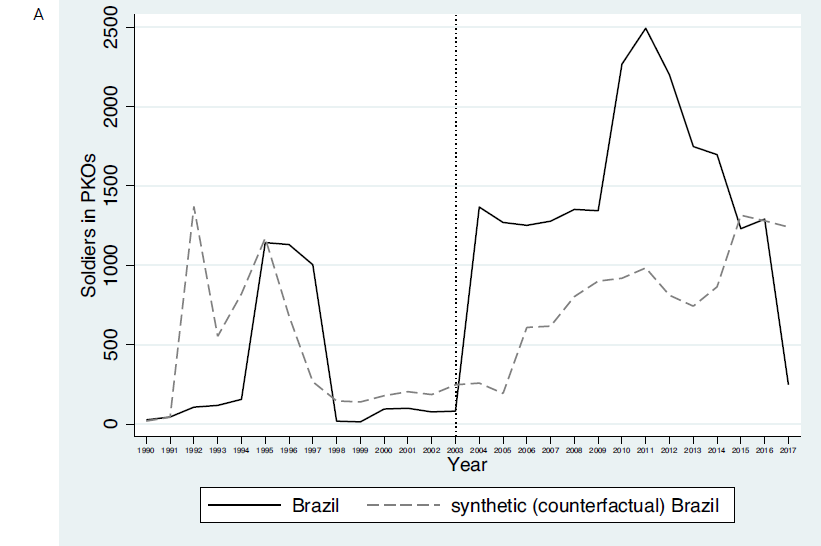

The initial argument about overstretch was developed by pairing Brazil with a counterfactual without Lula in the 2003 international context and showed an increase in key foreign policy indicators (Schenoni et al. 2022). Here, we use two relevant indicators of Brazilian overstretch in the diplomatic and security dimension to replicate the analysis of Lula's third election: the expansion of the Brazilian diplomatic representations and the increase in the participation of the country's troops in UN peacekeeping operations (PKOs). We reproduce figures 1 and 2 for the 2003 election and 3 and 4 for the 2023 election.

The synthetic control method (SCM) we use is a statistical technique used to estimate the counterfactual scenario of an intervention when random assignment is not possible. In the context of Brazil, the SCM involves constructing a synthetic version of the country using a weighted combination of indicators from other countries. These countries were selected based on their similarity to Brazil before the intervention in terms of characteristics that are predictive of the outcomes of interest, such as embassy increases and the deployment of troops. The goal is to create a synthetic Brazil that mimics the key factors influencing Brazil's trajectory before the intervention took place.

The weights assigned to the different countries in the synthetic control are determined by minimizing the differences between Brazil's observed pre-treatment values of the predictors and the corresponding values for the synthetic Brazil, which allows for a more accurate construction of the counterfactual Brazil, representing what might have happened in the absence of the intervention. By comparing the post-treatment outcomes of the actual Brazil with the synthetic control, the SCM offers insights into the causal effect of the increase in embassies and the deployment of troops. This method is particularly useful when randomized control trials are not feasible, as it offers a way to estimate what would have occurred under a different set of circumstances, using real-world data.

We also use the same countries and indicators as in the original study. The interpretation of the figures below should consider a significant treatment effect (Lula's rise in 2003 and 2023) when factual Brazil shows a considerably greater increase in the two selected variables during the post-treatment period. In other words, the solid line below (real Brazil) should move much further away from the dashed line (counterfactual Brazil) after the treatment, in this case, Lula's elections in 2003 and 2023. Furthermore, applying placebo tests allows us to confidently argue whether there was an excessive expansion of foreign policy.

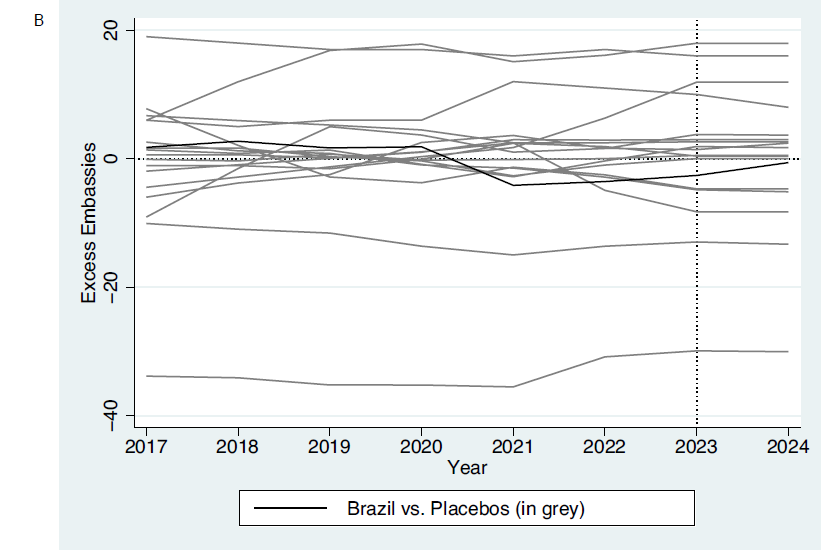

Figure 1. Number of embassies: Actual vs. counterfactual Brazil after Lula 2003. Source: Schenoni et. al (2022).

On the right side of Figure 1, we show the placebo test, running the same analysis with each of the 17 countries like Brazil, counting the number of excess embassies for each one. The results show that Brazil is among the few countries defined as on a positive trajectory, being the most affected by the 2003 treatment, namely the beginning of the Lula administration. The method used allows us to more robustly observe that the effect of Lula's rise on diplomatic expansion is significant. Several countries under the same international conditions could overstretch their foreign policies from 2003 onwards. However, Brazil expanded much more than expected without the effect of Lula's first election.

Between 2003 and 2010, Brazil increased the number of embassies from 96 to 127. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, there were 17 embassies in 2003, and 29 in 2010, placing Brasília among the most represented in the region. In addition to embassies and missions abroad, consular activities and participation in international organizations also increased. The number of governmental positions abroad jumped from 150 in 2002 to 217 in 2010, and the total number of diplomats rose from 997 to 1,405 in the same period. The chancellery budget as a whole also doubled its share of ministerial expenditures. This budget increase positively impacted Brasília's ability to offer cooperation to countries, including bilateral agreements with 113 countries during the period. The countries in which Brazil spent the most resources on bilateral cooperation during the period were Haiti, Mozambique, Cuba, Palestine, the United States, Chile, Argentina and Paraguay (COBRADI 2010). The areas that stand out in Brazilian bilateral cooperation are agriculture, education, defense, and health, with strong participation from federal companies and agencies such as Fiocruz (health) and Embrapa (agriculture). Below, we turn to the peacekeeping contributions.

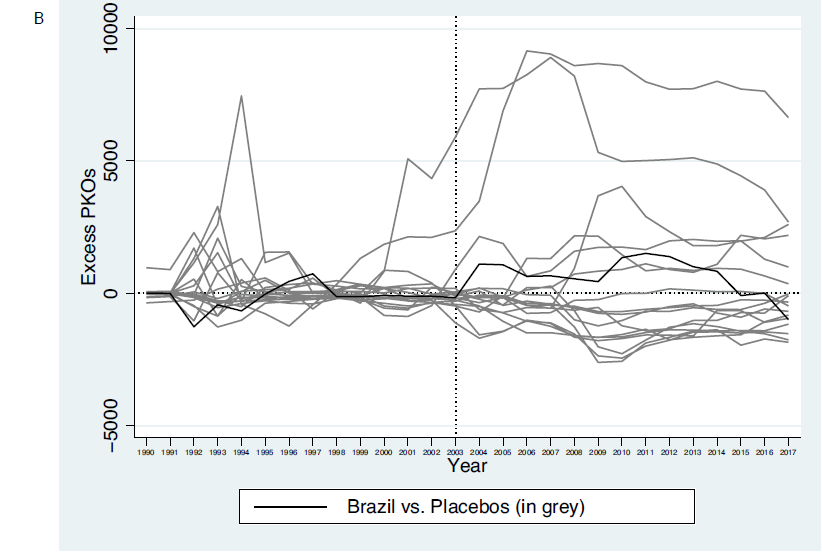

Figure 2. Number of Soldiers in PKOs: Actual vs. counterfactual Brazil after Lula 2003. Source: Schenoni et. al (2022).

Figure 2, on the left, highlights the significant impact of Lula on the number of troops available for peacekeeping operations. The country went from a few dozen troops to about 200 in 2003, advancing to 1,400 already in 2004, and 2,500 troops when overstretch started to loom large in 2012. The synthetic comparison remains at around 150 and in a decreasing trend—meaning that a county just like Brazil alongside relevant indicators would not have expanded that much, even under the Chinese-led economic boom. The placebos on the right side of Figure 2 show a significant variation in contributions to PKOs across the countries in the sample, suggesting overlapping elements from 2003 onwards that could affect the expected trajectories of countries other than Brazil.

Brazil, together with Germany, Japan and India, forms the G4, a coalition of countries seeking to reform the UNSC with permanent seats for its members. While the first two partners in G4 are among the largest financial contributors to UN peacekeeping missions, India is one of the countries that provides the most troops in the world.

During Lula's first term, sending troops to Haiti in 2004 was responsible for the exponential increase in Brazil's contribution to the UN's collective security. At the request of the United States, Brazil assumed the military leadership of a UN peacekeeping mission for the first time, representing Brazil's most forceful action in its bid for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Between 2004 and 2017, Brazil committed 37,000 soldiers and spent approximately R$ 2 billion (the UN reimbursed one-third of this amount). Before Haiti, Brazil's largest deployment had been for the mission in Angola (UNAVEM III), totaling 4,174 soldiers. Brazil, together with Germany, Japan and India, forms the G4, a coalition of countries seeking to reform the UNSC with permanent seats for its members. While the first two partners in G4 are among the largest financial contributors to UN peacekeeping missions, India is one of the countries that provides the most troops in the world. Thus, Brazil needed to convert its rhetoric of reforming the international system into material investment, convincing the international community of its capacity to provide security and promote development.

A retraction in Brazilian foreign policy accompanied the 12 years following Lula's expansion (Zanini, 2017; Malamud, 2017), frustrating Brazil's aspirations to be one of the poles of a new global order. Credit for international investment plummeted, and some embassies were unable to pay for essential services. Brazil accumulated debts with international organizations and courts, leaving it on the brink of suspension from several international bodies. These revealing events demonstrated the limits of Brazilian ambition, whose foreign policy retraction was as notable as its previous expansion (Cervo & Lessa 2014; Kalout & Degaut 2017; Malamud 2017; Schenoni & Leiva 2021; Nolte & Schenoni 2024). If we replicate the analyses now, we can clearly see that this overstretch has not happened again in Lula’s return to the Presidency in 2023.

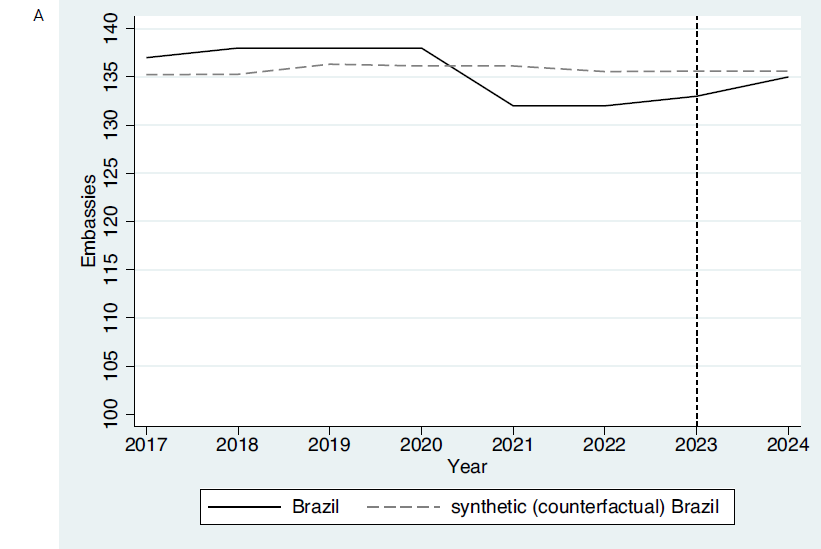

Figure 3. Number of embassies: Actual vs. counterfactual Brazil after Lula 2023. Notes: Formulated by the authors using the Stata package "synth2." Sources: The number of embassies comes from the Lowy Institute Global Diplomacy Index (https://globaldiplomacyindex.lowyinstitute.org/country_ranking) and data about countries from World Bank data (https://databank.worldbank.org/).

The left side of Figure 3 reveals three interesting movements. The first is the maintenance of a significant number of embassies, above the estimate of the counterfactual Brazil in part of the series, placing the country among the ten with the most embassies in 2024 (Global Diplomacy Index 2024). Second, the country peaked in embassies in 2017, only to decline in the following years. In 2020, under the Bolsonaro government (2019-2022), the Foreign Ministry closed seven embassies and opened one in Bahrain in 2021, resulting in a small negative balance of embassies. Third, when Lula takes office in 2023, there is a slight increase in embassies, with the recreation of the embassy in Sierra Leone and the creation of another in Rwanda, while the trajectory of the counterfactual Brazil remains stable. It is important to note that this study only covers one year after the treatment occurrence, making it difficult to observe whether there is an effect in the long term. However, on the right side of Figure 3, the placebo tests increase the expectation that there will be no significant effect from the 2023 election, given the lack of salience in the trajectory of the growth of embassies in Brazil when compared to the trajectories of other countries in the placebo tests. Below, we present the replication for the deployment of troops.

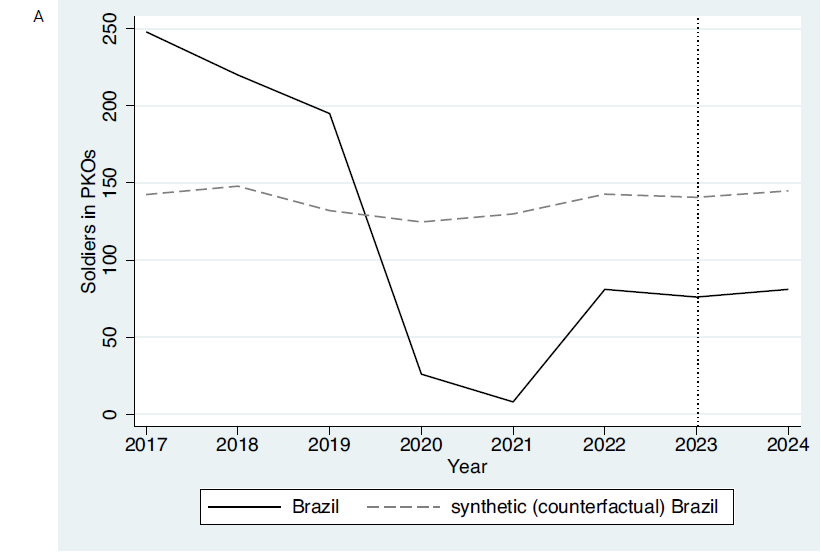

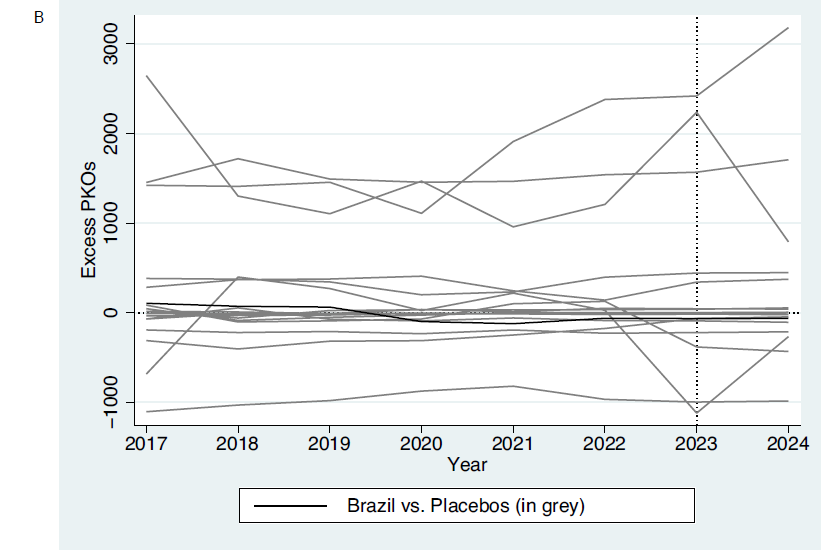

Figure 4. Number of Soldiers in PKO: Actual vs. counterfactual Brazil after Lula 2023. Notes: Formulated by the authors using the Stata package "synth2." Sources: The number of soldiers in PKOs comes from United Nations PeaceKeeping data (https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/data) and data about countries from World Bank data (https://databank.worldbank.org/).

Figure 4 more clearly demonstrates the absence of an overstretch effect on the country's contribution to collective security in this manner. On the left side of the figure, starting in 2017, we observe the beginning of the decline of Brazil's troop contribution, in bold, and falling below counterfactual Brazil since 2019, in dashed line. It was precisely in 2017 that President Michel Temer (2016-2018) ended Brazil's participation in the UN mission in Haiti. Lula's election in 2023 does not appear to change the trend of low participation of Brazilian troops, a fact also evidenced by the placebo tests in the figure above, whose trajectory in bold is one of the lowest in the sample. Corroborating the results shown in Figure 4, the refusal to send troops to Haiti again in 2023, already in Lula's third term, reveals the low probability of expansion of foreign policy in this issue. In a scenario of budgetary shortages, the Brazilian government claimed that the international community did not provide the conditions for Haiti's development and that sending troops would not be efficient. Brazil adjusted its ambition to the level of its ability to maintain a stable material commitment to the international public goods supply, eliminating the possibility of overstretching.

This adjustment could be because Lula changed or because the international environment changed, since the 2003 shock was initially conceptualized as an interaction of both events. At the international level, there is much less acceptance of the multipolar narrative of Lula's first terms, combining a more limited space for action by emerging countries. Domestically, the country is still struggling to recover from the economic depression that began in 2015, Congress is more conservative and ideologically polarized (Zucco & Power 2024), and the Executive no longer controls the budget (Faria 2022), making it challenging to invest national resources in foreign policy.

OVERSTRETCH OR RELUCTANT RECOIL?

To evaluate whether Lula's current foreign policy represents an overstretch or strategic shrinking, one must look at the relation between actions and speech or "words and deeds" (Jenne et al. 2017). Lula has been vociferous and sometimes polemic in his treatment of Ukraine and active in the environmental agenda by organizing a G20 and trying to play a central role in the Venezuelan crisis. However, Brazil's actual impact (and investment) was modest on all these fronts.

In the background, one must consider the third Lula administration's focus on straddling the divide between the West and the rest without disturbing key partnerships. Renewing relationships with traditional allies, such as the United States and European nations, points toward a more collaborative approach. The strategic patience with which Lula has dealt with Javier Milei's Presidency in Argentina illustrates this emphasis on diplomacy over confrontation very well, contrasts with the more aggressive stances of some other global leaders (usually on a more emboldened Right) and suggests a recalibration of priorities that may mitigate the concerns of overstretch.

…one must consider the third Lula administration's focus on straddling the divide between the West and the rest without disturbing key partnerships. Renewing relationships with traditional allies, such as the United States and European nations, points toward a more collaborative approach.

Moreover, Lula's administration is leveraging multilateral organizations and forums to promote its agenda, recognizing Brazil's limitations and the significance of collective action. By focusing on partnerships rather than isolated initiatives, Lula may be avoiding the pitfalls of overextension and aligning more closely with global movements while ensuring the sustainable representation of Brazil's interests.

But what do we know? We still have little data and workforce to measure these trends and provide an analysis like that of PKO and embassies shown above. Brazil needs to invest more in understanding Foreign Policy in Numbers, a trend where some major works have made inroads for a decade (e.g., Amorim Neto 2014; Rodrigues et al. 2019) but have been slow to take off. In particular, the systematic analysis of foreign policy discourse seems underexplored (given available techniques for web scraping and content analysis of big data) which might illustrate a fundamental gap between bombastic speech and a reality of shrinking foreign policy investment, which we call reluctant recoil.

CONCLUSION

While Lula's past terms displayed characteristics of foreign policy overstretch, the early indicators of his third term suggest a potential shift towards a more strategic and realistic foreign policy framework. Although his rhetoric continues to feature higher values and harsh adjectives, his practice has become less enthusiastic. Can this change be credited to political learning or human aging? Or is it shaped more broadly by structural forces, such as international hardening, where the global environment offers less room for Brazil's soft power, and domestic weakening, as financial, political, and military restrictions (including the “bolsonarization” of the armed forces) constrain its ambitions?

Regardless, by prioritizing environmental issues, revitalizing traditional alliances, and emphasizing multilateral cooperation, Lula may be navigating a path that circumvents the excessive ambitions of his previous administrations. This approach addresses the challenges posed by an evolving global scenario and ensures that Brazil's foreign policy remains both ambitious and sustainable. However, factors such as political learning or the inevitable effects of human aging, including energy depletion and attention shifts may also influence this recalibration.

As his third term progresses, the effectiveness of this realignment will be critical in determining Brazil's role on the world stage and the extent to which it can fulfill its international aspirations without succumbing to the adverse effects of overstretch. It is to be regretted, however, that analysts in Brazil are lagging in a computational revolution on big data and AI that can allow for a methodological turn in how we do foreign policy analysis. Some of the models above could be generalized to the analysis of basically any change we wanted to trace back to 2023. We hope more such analyses will come.

Notes

[1] See https://sites.usp.br/pen/en/home-english/.

Amorim Neto, Octavio. 2014. De Dutra a Lula: a condução e os determinantes da política externa brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier.

Burges, Sean & Fabricio Bastos. 2017. "The Importance of Presidential Leadership for Brazilian Foreign Policy." Policy Studies 38 (3): 277-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2017.1290228.

Cason, Jeffrey & Timothy Power. 2009. “Presidentialization, Pluralization, and the Rollback of Itamaraty: Explaining Change in Brazilian Foreign Policy Making in the Cardoso-Lula Era.” International Political Science Review 30 (2): 117-140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512109102432.

Cervo, Amado Luiz & Antônio Carlos Lessa. 2014. “O declínio: inserção internacional do Brasil (2011–2014).” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 57 (2): 133-151. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329201400308.

IPEA. 2010. “Cooperação Brasileira para o Desenvolvimento Internacional.” Relatório COBRADI. https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/livros/livros/livro_cooperacao_brasileira_ed02a.pdf.

Danese, Sérgio França. 2017. “Brasil, América del Sur, y el resto del mundo.” La Nación, 15 de julio de 2017. https://www.lanacion.com.ar/opinion/brasil-america-del-sur-y-el-resto-del-mundo-nid2042983/.

Faria, Rodrigo Oliveira de. 2022. “O desmonte da caixa de ferramentas orçamentárias do Poder Executivo e o controle do orçamento pelo Congresso Nacional.” SciELO Preprints. https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.4875.

Lowy Institute. 2024. Global Diplomacy Index. https://globaldiplomacyindex.lowyinstitute.org/.

Iglesias, Roberto Magno & Pedro da Motta-Veiga. 2002. "Promoção de Exportações via Internacionalização das Firmas de Capital Brasileiro." In O desafio das exportações, Armando Pinheiro, Ricardo Markwald & Lia Pereira (eds.): 367-446. Rio de Janeiro: BNDES. https://web.bndes.gov.br/bib/jspui/bitstream/1408/2064/1/Livro%20completo_O%20desafio%20das%20exporta%C3%A7%C3%B5es_P.pdf.

Jenne, Nicole, Luis Leandro Schenoni & Francisco Urdinez. 2017. "Of Words and Deeds: Latin American Declaratory Regionalism, 1994–2014." Cambridge Review of International Affairs 30 (2-3): 195-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2017.1383358.

Kalout, Hussein & Marcos Degaut. 2017. Brasil, um país em busca de uma grande estratégia. Brasília: Secretaria de Assuntos Estratégicos, Presidência da República. DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.33907.32801.

Malamud, Andrés. 2005. “Presidential Diplomacy and the Institutional Underpinnings of Mercosur. An Empirical Examination.” Latin American Research Review 40 (1): 138-64.

Malamud, Andrés. 2017. "Foreign Policy Retreat: Domestic and Systemic Causes of Brazil’s International Rollback." Rising Powers Quarterly 2 (2): 149-168. http://hdl.handle.net/10451/28469.

Mariano, Marcelo & Haroldo Ramanzini. 2023. "Possibilidades de Monitoramento e Avaliação da Política Externa Brasileira." Revista Tempo do Mundo 33: 169-203. https://doi.org/10.38116/rtm33art6.

Nolte, Detlef, Luis Leandro Schenoni. 2024. "To Lead or Not to Lead: Regional Powers and Regional Leadership." International Politics 61: 40-59. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00355-8.

Rodrigues, Pietro, Francisco Urdinez & Amâncio de Oliveira. 2019. “Measuring International Engagement: Systemic and Domestic Factors in Brazilian Foreign Policy from 1998 to 2014.” Foreign Policy Analysis 15 (3): 370-391. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orz010.

Ricupero, Rubens & Fernando Barreto. 2007. "A importância do investimento direto estrangeiro do Brasil no exterior para o desenvolvimento socioeconômico do país." In Internacionalização de Empresas Brasileiras: perspectivas e riscos, André Almeida (Org.): 1–36. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier.

Saggioro, Ana. 2012. "Internacionalização de empresas brasileiras durante o governo Lula: uma análise crítica da relação entre capital e Estado no Brasil contemporâneo." Tese de Doutorado, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro.

Schenoni, Luis L. 2017. "Brasil Contrae su Política Exterior." La Nación, 12 de julio de 2017. https://www.lanacion.com.ar/opinion/brasil-contrae-su-politica-exterior-nid2041884/.

Schenoni, Luis L. & Diego Leiva. 2021. "Dual Hegemony: Brazil Between the United States and China." In Palgrave Studies in International Relations, Florian Böller & Welf Werner (eds.): 233-255. London: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74505-9_12.

Schenoni, Luís, Pedro Feliú, Dawisson Belém-Lopes & Guilherme Casarões. 2022. "Myths of Multipolarity: Sources of Brazil's Foreign Policy Overstretch." Foreign Policy Analysis 18 (1). https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orab037.

Sotero, Paulo and Leslie Elliott Armijo. 2007. "Brazil: To Be or Not to Be a BRIC?" Asian Perspective 31 (4): 43-70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42704608.

Tavares, Márcia. 2006. "Investimentos brasileiros no exterior: panoramas e considerações." CEPAL, Serie Desarrollo Productivo 172: 1-31.

Zanini, Fábio. 2017. Euforia e Fracasso do Brasil Grande: Política Externa e Multinacionais Brasileiras na Era Lula. São Paulo: Contexto.

Zucco, Cesar & Timothy Power. 2024. "The Ideology of Brazilian Parties and Presidents: A Research Note on Coalitional Presidentialism Under Stress." Latin American Politics and Society 66 (1): 178-188. DOI: 10.1017/lap.2023.24.

Submitted: November 29, 2024

Accepted for publication: December 5, 2024

Copyright © 2024 CEBRI-Journal. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original article is properly cited.