We examine the ideas shaping Javier Milei’s foreign policy within the broader context of the global rise of the new far-right. Our argument is that Milei’s rhetoric and stance align with this global far-right movement, characterized by cultural conservatism and a deep skepticism towards global governance. However, this global scenario only tells part of the story as Milei’s foreign policy also carries the imprint of Argentina’s distinctive diplomatic standpoint and domestic realities.

Since Javier Milei took office as Argentina's President in December 2023, the country's foreign policy has notably shifted, reflecting a bold departure from established norms. On pivotal issues like the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, Milei has unambiguously sided with the United States and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), signaling a deepening of ties with Western powers. Meanwhile, the once robust ties with China, a hallmark of previous administrations, have now taken a back seat, becoming more technical in nature. Relations with Brazil are strained by disagreements and a noticeable absence of dialogue between two leaders who have yet to meet face-to-face. On the multilateral stage, the focus on human rights and gender, once central to Argentina's diplomacy, has faded. Climate-related issues are now considered politically fraught and ideologically suspect within the new policy scenario, and diplomats have been instructed to avoid Agenda 2030 initiatives.

This emergent global far-right, often propelled by dissatisfaction with traditional elites and frustration with global institutions, positions itself as a counterweight to the so-called liberal international order and the progressive values that have underpinned the post-World War international system.

Milei’s policy choices, however, signal more than a domestic shift in Argentina’s political scenario. It echoes the broader surge of a new right-wing constellation reshaping the global scene, from Donald Trump in the United States and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil to Giorgia Meloni in Italy and the Chega! and Vox parties in Portugal and Spain, respectively. This emergent global far-right, often propelled by dissatisfaction with traditional elites and frustration with global institutions, positions itself as a counterweight to the so-called liberal international order and the progressive values that have underpinned the post-World War international system.

In this article, we examine the ideas shaping Javier Milei’s foreign policy within the broader context of the global rise of the new far-right. Our central argument is that Milei’s rhetoric and stance align with this global far-right movement, characterized by cultural conservatism and a deep skepticism towards global governance. However, this global scenario only tells part of the story as Milei’s foreign policy also carries the imprint of Argentina’s distinctive diplomatic standpoint and domestic realities. This dual dynamic—of aligning with a global right-wing resurgence while grappling with Argentina’s unique legacy—adds a layer of complexity to understanding the country’s evolving role on the world stage.

The article is divided into two sections, with a concluding analysis. The first section analyzes the nature of the new global far-right, emphasizing its complex and fragmented character, which resists a unified narrative and, instead, reveals overlapping traits that shift according to local/regional contexts. The second section delves into Javier Milei’s foreign policy, focusing more on the ideological underpinnings rather than specific policy initiatives. The conclusion reflects on the implications of this emerging trend and its potential short- and medium-term effects on Argentina’s position in the global arena.

THE GLOBAL FAR-RIGHT: DISSIMILAR GEOPOLITICS, ANALOGOUS NARRATIVES

Over the past decade, far-right narratives have resurfaced, shifting public conversation and placing immigration, national sovereignty, and cultural identity at the heart of national debates. As geopolitics takes center stage, these narratives increasingly shape public opinion and policy decisions. Prominent figures and parties such as Vladimir Putin, Vox, Alternative for Germany, Donald Trump, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Viktor Orbán, Giorgia Meloni, Marine Le Pen, and lesser-known leaders like Petr Fiala in the Czech Republic, Andrej Plenković in Croatia, Petteri Orpo in Finland, Kyriakos Mitsotakis in Greece, and Ulf Kristersson in Sweden exemplify this resurgence. In Latin America, leaders such as Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, José Antonio Kast and Evelyn Matthei in Chile, Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, Daniel Noboa in Ecuador, Alejandro Giammattei in Guatemala, Dina Boluarte in Peru, and Rodrigo Chaves in Costa Rica reveal that the region is also navigating this ideological wave.

These right-wing leaders, however, are far from monolithic and exhibit considerable variation in their economic standpoints, foreign policies, and geopolitical stances—from pro-trade to protectionism, from pro-China to anti-China and from pro-NATO to pro-Russian. Yet, beyond these different notes, there is a discernible unifying theme across the spectrum, namely anti-globalism. This manifests in various forms, from skepticism towards global governance to a broader rejection of the liberal, rules-based order that has characterized the post-World War II era. For these leaders, globalism represents a dilution of national sovereignty and a threat to traditional values, prompting them to advocate for a world where nation-States, rather than global institutions, hold the reins of power.

Some scholars have referred to this phenomenon as the Reactionary International (Tokatlian 2018; de Orellana & Michelsen 2019; Sanahuja & López Burian 2020; de Orellana, Michelsen & Buranelli 2023). The label refers to a concerted effort to dismantle or undermine the institutions and norms that have promoted open borders, human rights, cultural recognition, non-discrimination, and environmental cooperation, among other principles. The United Nations 2030 Agenda, with its ambitious Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), has increasingly become a focal point of criticism for far-right leaders around the world. For them, the Agenda represents the epitome of globalist overreach—a perceived imposition of international norms and priorities that, in their view, threaten national sovereignty and traditional values.

For many right-wing leaders, national identity lies also at the center of their political agenda, driving both their organizational strategies and alliances. This emphasis on identity creates a dual dynamic: internally, it fosters cohesion by rallying supporters around shared values and a collective sense of purpose. Their base typically embraces this internal unity, or singularity, with little resistance; externally, however, their solidarity is often forged through exclusion, uniting their followers in opposition to those deemed as outsiders or threats to the nation's identity.

This heightened focus on national identity explains why the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe marked a watershed moment for the far-right movement across the continent. The influx of refugees served as a catalyst, intensifying fears about the preservation of national identity and accelerating the rise of far-right sentiments. As Stefanoni (2019; 2021) noted, the crisis not only heightened these anxieties but also provided a platform for the legitimization of Renaud Camus' controversial thesis of the Great Replacement, which posits that native European populations are being systematically replaced by immigrants.

By prioritizing high-stakes issues, far-right leaders effectively shift the focus away from everyday politics, reinvigorating the realm of high politics.

Moreover, far-right leaders often weave a narrative around security, framing it as essential to safeguarding the populace from perceived disruptive forces (Hibbing 2020; 2022). Central to their agenda is the defense of a nation's historical core, a driving force for both leaders and their supporters. This focus translates into “(…) support for defense spending (Trump), opposition to outside influences (Farage), tough sentences for criminals (Duterte), support for historically dominant customs, language and religion (Modi) and restrictions on immigration” (Hibbing 2022, 60). By prioritizing high-stakes issues, far-right leaders effectively shift the focus away from everyday politics, reinvigorating the realm of high politics.

Similar discursive strategies also serve as a common thread. For instance, leaders employ political incorrectness to signal sincerity, authenticity, or blunt honesty. As Souroujon (2022, 115) puts it, political incorrectness

allows miseries, prejudices and intolerances, which were previously hidden in the private sphere, to return to the public space with a reinvigorated legitimacy, as aggressive rhetoric against minorities, misogyny, violent attacks on political opponents, and bellicose speeches (…) permeate with legitimacy and pride certain expressions that were previously kept secret.

In addition to their ability to harness social indignation (Stefanoni 2021), far-right leaders employ a rhetoric of resentment that relies heavily on a populist “us-versus-them” narrative. On the global stage, these leaders amplify local grievances by connecting them with international dynamics. They often portray domestic elites as akin to foreign powers or link the national “people” to regional or global counterparts, extending their narrative beyond national borders (Chryssogelos 2019). This approach creates a broad array of perceived threats, which can include elites, political parties, economic sectors, international bureaucracies, or even entire countries. Leaders also target values, symbols, and beliefs—such as religious diversity, globalization, Western ideals, human rights, and multilateralism—as well as institutions like parliaments, courts, and international organizations. Moreover, they often frame these threats within specific historical or political contexts, such as political shifts, post-war periods, or ideological turns (Verbeek & Zaslove 2017; Jenne 2021; Özpek & Tanriverdi Yaşar 2018).

Finally, religion plays a crucial role, with the authority of various churches—whether Catholic, Evangelical, Pentecostal, or Methodist—acting as a unifying force. This centrality provides a framework that shapes both social and political narratives. A prominent theme is the defense of the “traditional family” against gender ideologies perceived as contrary to national values and traditional norms. Essentially, religion is leveraged to reinforce conservative values and reshape the concept of nationalism.

In Latin America, these dynamics resonate strongly with the region’s historical and social fabric (Sanahuja & López Burian 2020; 2024). This is evident in the far-right leaders' broad rejection of regional bodies like UNASUR, CELAC, and MERCOSUR. These leaders often dismiss pluralism and instead romanticize authoritarian regimes, portraying past dictatorships as defenders of the “nation” against the perceived threat of “communism.” Additionally, the region's historical tendencies toward the concentration and centralization of power in institutions and small circles are crucial to understanding its specificities. Meanwhile, the far-right's international outreach in Latin America often operates in alignment with Trump’s United States, with Milei’s Argentina and Bolsonaro’s Brazil serving as key examples. Appeals to a Western identity and the U.S. role in “saving the West” are prominent in the rhetoric of these crusaders (Sanahuja & López Burian 2020; Beasley et al. 2001; Malacalza 2024).

MILEI IN THE MIRROR OF THE GLOBAL FAR-RIGHT

In what ways does Javier Milei embody the defining traits of the global right? As previously noted, a hallmark of the global far-right is its staunch rejection of globalism. Here, Milei's worldview is fundamentally at odds with the international liberal order, which he criticizes for its perceived alignment with socialism, multiculturalism, feminism, and the global energy transition, among others (Página12 2024a). Central to his critique is Agenda 2030, which he views as a vehicle for imposing what he terms a global social justice agenda—anathema to his libertarian principles. In his view, institutions like the United Nations are enclaves of international bureaucracy akin to domestic elites, fostering an anti-multilateral, anti-gender, and anti-decarbonization stance. Notably, Milei's skepticism extends to climate change itself, marking a more radical departure from mainstream European conservatism.

Milei’s anti-globalism is clearly reflected in the country’s approach to multilateral forums. Officials and diplomats are reluctant to include gender-related language or discuss matters related to the 2030 Agenda, including climate change mitigation and adaptation. At the Organization of American States (OAS), for instance, Argentina recently opposed a resolution condemning sexual violence in Haiti. Additionally, the country refused to sign the United Nations global pandemic treaty at the World Health Organization, with Foreign Minister Diana Mondino asserting that “Argentina will not allow an international body to infringe upon our sovereignty, much less to lock us up again” (@DianaMondino, June 9, 2024). These bold moves under Milei's administration mark a departure from Argentina's historical commitment to multilateral diplomacy.

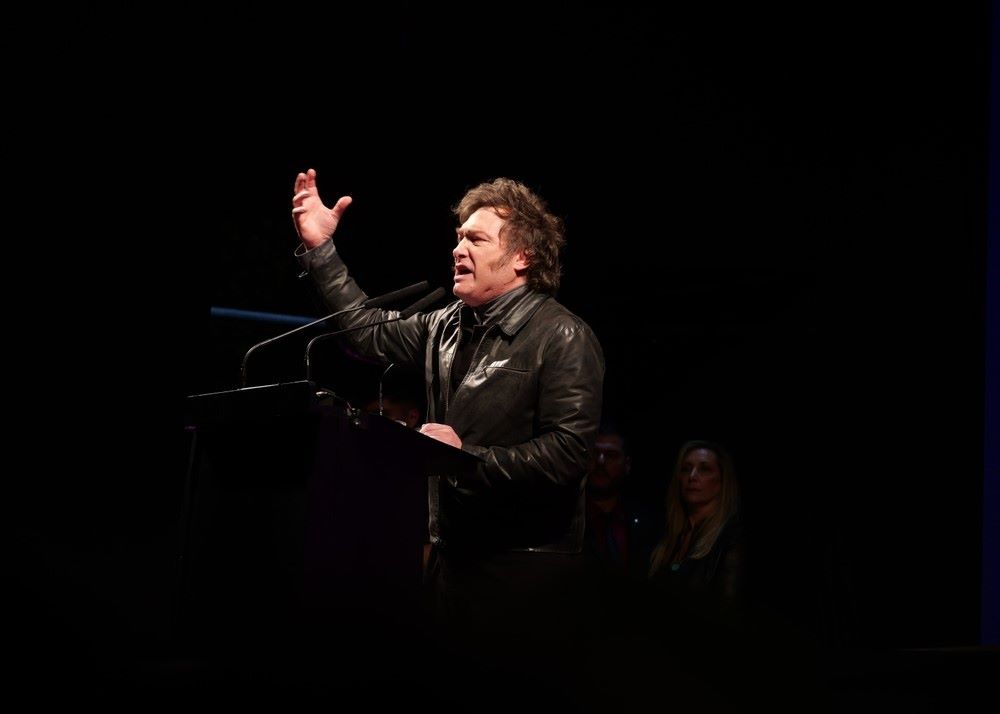

Also, in line with this anti-globalist sentiment, Milei has been notably focused on forging connections with anti-establishment leaders, libertarians, big techs, and hard-right figures. This strategy highlights his intent to bypass traditional diplomatic channels, positioning himself alongside like-minded ideologues on the global stage. Often referred to as “CEO diplomacy” or “meet and greet diplomacy,” this approach underscores Milei’s ambition to build alliances and exert influence outside conventional political frameworks, potentially steering Argentina’s foreign policy in new and unconventional directions.

Milei’s alignment with the West, and particularly with the United States, serves as a key indicator of his international stance. This orientation not only underscores his geopolitical strategy but also reveals the contours of his global identity. This is evident in the agreed-upon roadmap with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) aimed at advancing Argentina's accession process and in its steadfast commitment to finalizing the Mercosur-European Union trade agreement. In numerous private appearances, Milei has even signaled that “the West is under threat” (Milei 2024), positioning Argentina as a potential stronghold in its defense.

Much like other populist leaders, Milei's rhetorical style is striking, especially in his extended forays on social media, where he actively engages in provoking his audience (…), which seems to resonate with a particular segment of voters while systematically undermining his opponents.

Much like other populist leaders, Milei's rhetorical style is striking, especially in his extended forays on social media, where he actively engages in provoking his audience. His approach exhibits a penchant for insults and coarse language, which seems to resonate with a particular segment of voters while systematically undermining his opponents. Milei does not merely engage in the debate; he targets his adversaries with a directness that leaves little room for nuance.

Like other right-wing populist leaders, Milei engages with religion through a distinctly political lens, albeit with less institutional fervor than some of his peers. Despite his Catholic roots, Milei has demonstrated a notable interest in Judaism, with his alignment with Israel serving as a key indicator of this stance. His administration’s plan to relocate Argentina’s embassy to Jerusalem is a striking example—widely interpreted in diplomatic circles as a costly signal of allegiance to the Israeli cause. Historically critical of human rights violations in the West Bank by Israel, Argentina now aligns itself with Benjamin Netanyahu's administration at the United Nations.

Yet despite these standpoints, Milei distinguishes himself in key areas from the hard-core far-right, particularly on identity-related issues, such as migration. Unlike Europe and the United States, where demographic issues such as migration and multiculturalism are highly politicized, Argentina faces less acute demographic pressures. This relatively subdued context allows Milei to adopt a more permissive stance on immigration, though his approach remains without a fully developed policy framework.

In trade policy, Javier Milei stands out with a notably more liberal approach than many of his right-wing peers, who typically champion re-industrialization and protectionist strategies against Chinese imports. Milei’s perspective reflects a distinct departure from the prevailing trend among right-leaning leaders, emphasizing a freer market stance in an era of increasing economic nationalism. In this sense, he distances himself from protectionist agendas espoused by figures such as Le Pen, leaning instead towards a position favoring globalization without embracing globalist principles—a stance akin to Meloni of Brothers of Italy or the Alternative for Germany (AfD). In this sense, Milei's alignment with Meloni's Brothers of Italy orientation is strikingly evident. He shares a robust pro-trade stance, supports Israel, and aligns closely with the United States and NATO (Delicado Palacios 2024)—a stance mirrored by right-wing factions in Poland's PiS and Spain's Vox. His approach to international relations situates him firmly against Russia, reflecting a broader alignment with conservative European attitudes. Conversely, Milei’s position on China underscores a nuanced evolution (Lejtman 2023). Initially espousing strident anti-Chinese sentiments, his views have since moderated, aligning him closer to Meloni or Le Pen than to the more conciliatory approaches of Hungary’s or Bulgaria's right-wing leaders.

Much like his counterparts, Milei shows little enthusiasm for summit diplomacy, international organizations, or the painstaking negotiation of global rules. For someone intent on dismantling State regulations at home, the idea of crafting international regulations seems anathema. After all, why would a champion of domestic deregulation find value in international regulation? And why would someone skeptical of public goods at home suddenly endorse their provision on a global scale? To Milei, international bureaucracy smacks of a socialist agenda—a roadblock to Argentina’s prosperity. His disregard for sustainable development goals and environmental commitments is entirely consistent with this outlook. Also, Milei’s worldview diverges sharply from the traditional Westphalian or interstate model. Instead, it’s a landscape populated on one side by corporate titans, investors, bankers, asset managers, and other “heroes,” as he lauded them in Davos, and on the other by progressives, collectivists, communists, authoritarians, and the many faces of “woke” culture (Merke 2024).

In this sense, there is something distinctly peculiar in the way Milei perceives the international society. When he addresses foreign affairs, he struggles to acknowledge that his voice represents the Argentine State. Instead, he is content with the belief that he speaks solely for himself, not even for his cabinet (Sugarman 2024). This individualistic stance stands in stark contrast to the principles that underpin international relations. Any international society fundamentally involves a “second-order” social structure composed of “first-order” entities, the national societies. This concept, typically ingrained in the thinking of diplomats and political leaders, forms the bedrock of global diplomacy. It is through this lens that States interact, negotiate, and cooperate, recognizing each other as sovereign entities within a complex web of international norms and agreements. Yet Milei appears disconnected from this perspective, seemingly foreign to a Westphalian habitus. The Westphalian system, with its emphasis on State sovereignty and the legal equality of States, has shaped international relations since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. By denouncing the State as “the evil one” (Alconada Mon 2023), Milei implicitly rejects the very foundation of this system. He views the State not as a legitimate actor in a society of States but as a malevolent force. “The State can therefore be defined as the organization of political means based on the systematization of the predatory process over a given territorial area. A sort of mafia with legal backing” (Milei & Giacomini 2019, 43).

It is through multilateral frameworks that global challenges are addressed, from climate change to international security. Milei's implicit rejection of the State's legitimacy in the international arena disrupts this cooperative spirit.

This viewpoint fundamentally undermines the principles of multilateralism, which rely on cooperation and mutual recognition among States, not merely among individual leaders sharing common ideological standpoints. It is through multilateral frameworks that global challenges are addressed, from climate change to international security. Milei's implicit rejection of the State's legitimacy in the international arena disrupts this cooperative spirit. In essence, Milei's approach not only isolates himself from the established norms of international diplomacy but also poses a challenge to the collaborative ethos that underpins multilateralism.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Milei is incomparable. Not only because of his style, his ideological mix and the characteristics of his political coalition, but also because all this must be adapted to the Argentine national context and history. However, an exceptionalist reading prevents us from seeing the forest. Of course, the far-right is heterogeneous but, from some ideological references and communication and stylistic maneuvers, it also has features in common. We have mentioned and characterized some of them as anti-globalism, anti-communism, the cultural battle, a style of political communication (political-discursive incorrectness) which they disguise as brutal honesty and minarchism around a narrative of law and order as opposed to a “disruptive other.” Moreover, they themselves feel part of the same movement made up not only of parties and leaders, but also of a dense network of associations, foundations and think tanks on both sides of the Atlantic. We must also bear in mind that all ideologies, because of the impact of national and international contexts and the very evolution of political thought and cultures, are constantly under construction, influencing and redefining each other. As Floria (1994, 4) argues: “History is a graveyard of ideologies. The social journey transforms them. They take on apparently different physiognomies, they go through dissimilar forces and situations”. This family has welcomed Milei with open arms. The Argentinian President often wanders into conservative redoubts, receiving small awards and hospitality. At the Europa Viva 24 Summit he was the guest of honor and rubbed shoulders with the crème de la crème of the global far-right: from Marine Le Pen, Abascal, Kast and Orbán to Morawiecki, Ventura, Giorgia Meloni, Roger Severino and Matt Schlapp, and Israeli minister Amichai Chikli (Forti 2024), just to mention a few.

Everyone is attentive to the ups and downs of this character, not only because of his transgressive style that to a certain extent equates them, but also because he is the first paleolibertarian to become the head of a State, which turns Argentina into a laboratory of political ideas. He is the first politician to argue that the State is a mafia and has come to destroy it from within[1]. Javier Milei's foreign policy thus epitomizes the complex interplay between global far-right movements and local political reality. While his rhetoric is aligned with global far-right trends, it is also shaped by Argentina's unique diplomatic and domestic landscape, as well as by a mix of conservative, liberal and libertarian ideas. The peculiarity of Argentina's historical and diplomatic context ensures that Milei's approach will also have unique characteristics.

In an increasingly complex world, where rigid alignments no longer bring the benefits of yesteryear and dogmatic posturing loses its utility, the countries of the Global South must be more careful than ever in their diplomacy and international strategies. However, the Argentine government seems to ignore this reality by adopting a bandwagon's posture that discards beneficial strategic alliances and arbitrarily decides which relations to privilege according to ideological lenses. This lack of prudence in foreign policy can only lead to undermine Argentina's position and credibility on the global stage.

Notes

[1]“I love, love being the mole inside the State. I am the one who destroys the State from the inside. Let's say, it's like being infiltrated into the enemy ranks. I hate the State so much that I'm willing to put up with these slanders both on myself and on my most loved ones, which are my sister and my dogs.” Interview with the American media The Free Press (Página12 2024b).

Alconada Mon, Hugo. 2023. “‘El Estado es la encarnación del Maligno’. Quién es y cómo piensa el economista que citó Javier Milei en su discurso inaugural.” La Nación, December 11, 2024. https://www.lanacion.com.ar/politica/el-estado-es-la-encarnacion-del-maligno-quien-es-y-como-piensa-el-economista-que-cito-javier-milei-nid11122023/.

Beasley, Ryan, Juliet Kaarbo, Charles F. Hermann & Margaret G. Hermann. 2001. “People and Processes in Foreign Policymaking: Insights from Comparative Case Studies.” International Studies Review 3 (2): 217-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/1521-9488.00238.

Chryssogelos, Angelo. 2019. “Europeanisation as De-politicisation, Crisis as Re-politicisation: The Case of Greek Foreign Policy During the Eurozone Crisis.” Journal of European Integration 41 (5): 605-621. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1544249.

Delicado Palacios, Ana. 2024. “Milei arrastra a Argentina a la sombra de EEUU e Israel.” El Salto, April 19, 2024. https://www.elsaltodiario.com/america-latina/milei-arrastra-argentina-sombra-eeuu-israel.

de Orellana, Pablo & Nicholas Michelsen. 2019. “Reactionary Internationalism: The Philosophy of the New Right.” Review of International Studies 45 (5): 748-767. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210519000159.

de Orellana, Pablo, Nicholas Michelsen & Filippo C. Buranelli. 2023. “The Reactionary Internationale: The Rise of the New Right and the Reconstruction of International Society.” International Relations 0 (0): 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/00471178231186392.

Fernández Meijide, Graciela. 2018. Entrevista a Juan Gabriel Tokatlian. Video posted November 22, 2018, by Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. YouTube, 28:38. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CAmgtR69uAg.

Floria, Carlos A. 1994. “El nacionalismo como cuestión transnacional: análisis político del nacionalismo en la Argentina contemporánea.” Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Latin American Program, Working papers 210. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999766674402121.

Forti, Steven. 2024. “Tomar Europa por las elecciones. La extrema derecha mundial en Madrid.” El Grand Continent, May 22, 2024. https://legrandcontinent.eu/es/2024/05/22/tomar-europa-por-las-elecciones-la-extrema-derecha-mundial-en-madrid/.

Hibbing, John. 2020. The Securitarian Personality: What Really Motivates Trump's Base and Why It Matters in the Post-Trump Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hibbing, John. 2022. “Populists, Authoritarians, or Securitarians? Policy Preferences and Threats to Democratic Governance in the Modern Age.” Global Public Policy and Governance 2: 47-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43508-021-00031-w.

Jenne, Erin. 2021. “Populism, Nationalism and Revisionist Foreign Policy.” International Affairs 97 (2): 323-343. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiaa230.

Lejtman, Román. 2023. “Giro geopolítico del Gobierno: Javier Milei comunicó por carta que Argentina renuncia a los BRICS.” Infobae, December 29, 2024. https://www.infobae.com/politica/2023/12/29/giro-geopolitico-del-gobierno-javier-milei-comunico-por-carta-que-argentina-renuncia-a-los-brics/.

Malacalza, Bernabé. 2024. “El espíritu de las Cruzadas y el fin de la diplomacia.” Clarín, January 29, 2024. https://www.clarin.com/opinion/espiritu-cruzadas-fin-diplomacia_0_86gtkPoP7Q.html.

Merke, Federico. 2024. “Entre el dogma y el interés.” Le Monde Diplomatique, 298. https://www.eldiplo.org/298-las-nuevas-relaciones-carnales/entre-el-dogma-y-el-interes/.

Milei, Javier. 2024. “Así fue el discurso del presidente Milei en Davos: ‘Occidente está en peligro’.” Video posted January 17, 2024, by CNN en Español. YouTube, 23:01. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hnZDVGCZxWE.

Milei, Javier & Diego Giacomini. 2019. Libertad, libertad, libertad. Buenos Aires: Galerna.

Özpek, Burak Bilgehan & Nebahat Tanriverdi Yaşar. 2018. “Populism and Foreign Policy in Turkey under the AKP Rule.” Turkish Studies 19 (2): 198-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2017.1400912.

Página12. 2024a. “Javier Milei sigue con su cruzada antiderechos: ahora propuso eliminar la Educación Sexual Integral.” Página12.com.ar, September 11, 2024. https://www.pagina12.com.ar/490483-javier-milei-sigue-con-su-cruzada-antiderechos-ahora-propuso.

Página12. 2024b. “¡Amo ser el topo dentro del Estado!...” Interview. Video posted June 7, 2024, by Página12. YouTube, 1:00. https://www.youtube.com/shorts/zZ26nMI8dns.

Sanahuja, José Antonio & Camilo López Burian. 2020. “Internacionalismo reaccionario y nuevas derechas neopatriotas latinoamericanas frente al orden internacional liberal.” Conjuntura Austral 11 (55): 22–34. https://doi.org/10.22456/2178-8839.106956.

Sanahuja, José Antonio & Camilo López Burian. 2024. “Latin America’s Neopatriots.” NACLA Report on the Americas 56 (1): 28-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2024.2323397.

Souroujon, Gastón. 2022. “La venganza de los incorrectos. La derecha radical populista y la política del resentimiento.” Revista Stultifera 5 (2): 101-123. https://doi.org/10.4206/rev.stultifera.2022.v5n2-05.

Stefanoni, Pablo. 2019. “El futuro como ‘gran reemplazo’. Extremas derechas, homosexualidad y xenofobia.” Nueva Sociedad 283: 95-110. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/nuso/nuso-283.pdf.

Stefanoni, Pablo. 2021. ¿La rebeldía se volvió de derecha? Cómo el antiprogresismo y la anticorrección política están construyendo un nuevo sentido común (y por qué la izquierda debería tomarlos en serio). Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno.

Sugarman, Jacob. 2024. “The World According to Javier Milei.” Buenos Aires Herald, August 14, 2024. https://buenosairesherald.com/world/international-relations/the-world-according-to-javier-milei.

Verbeek, Bertjan & Andrej Zaslove. 2017. “Populism and Foreign Policy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Cristóbal R. Kaltwasser, Paul A. Taggart, Paulina O. Espejo & Pierre Ostiguy (Eds.), 384-405. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Submitted: August 24, 2024

Accepted for publication: September 9, 2024

Copyright © 2024 CEBRI-Journal. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original article is properly cited.