Brazil’s G20 Presidency is an opportunity to deeply reshape our global economy and build political consensus on two fronts to address the twin challenges of climate and development: 1) a new energy sustainability and security package, focused on renewable energy, energy efficiency, transitioning away from fossil fuels, and managing competition in clean energy markets; and 2) a new reform vision for the financial system, focused on reimagining its institutions, norms, and terms of operation.

On June 23, 2023, President Lula addressed world leaders meeting in Paris during the Summit for a New Global Financial Pact (Brazil 2023a). His ambitious speech conveyed three key messages:

The 2024 G20 is an opportunity for Brazil to walk the talk on all of these issues–and there is strong hope that it will, given the ambitious agenda and priorities laid out by President Lula on December 13, 2023, during the first G20 meetings held under Brazil’s stewardship (the creation of a Global Mobilization against Climate Change is particularly encouraging). The G20 is a key multilateral forum that Brazil should leverage not just to demonstrate its leadership but to help design the post-Bretton Woods world, which should address both the climate crisis and inequality. What President Lula’s speech points to is the need to broker a consensus around a new modus operandi for our global economy and financial system, and the G20 is precisely the space to do that as the “premier forum for international economic cooperation.”[1]

The G20 is a key multilateral forum that Brazil should leverage not just to demonstrate its leadership but to help design the post-Bretton Woods world, which should address both the climate crisis and inequality.

Admittedly, the G20 often “muddles through.” G20 Presidencies typically result in lengthy statements or communiqués on a wide range of topics. These usually insist, throughout, on the “voluntary” nature of all the discussions that occurred, immediately limiting the impact that these statements could have by reminding their readers that G20 decision-makers do not feel bound by discussions held in this forum. But in some cases–as following the Global Financial Crisis–the G20 succeeds. When it does so, it produces strong political directionality on a pressing global issue: a signal is sent, the message is clear, and less caveats are used in the final written communiqués.

Brazil is taking over the G20 Presidency at an extremely sensitive time–characterized by many as that of the “polycrisis” (Whiting & Park 2023). Political and economic uncertainty reign amid rising debt (Gaspar, Poplawski-Ribeiro & Yoo 2023), growing inequalities, and more frequent and damaging climate disasters (Berman & Baumgartner 2023), against a backdrop of shifting power dynamics and lack of cooperation and consensus.

And yet, Brazil finds itself uniquely well positioned for success with its ambitious agenda:

What is needed from Brazil to deeply reshape our global economy and restore trust is building a political consensus on a new energy package and financial reform vision to address the twin challenges of climate and development. Brazil should focus on brokering a global political consensus on these two systemic fronts:

BUILDING A NEW CLEAN ENERGY DOCTRINE

As G20 countries collectively represent 76% of global greenhouse gas emissions (United Nations Environment Programme 2023), their leadership is essential to address the climate crisis. Building on the Indonesian and Indian G20 Presidencies, Brazil should use its Presidency to reframe the climate and energy policy landscape towards a goal of societal resilience and true security. Accelerating the clean energy transition and building much greater resilience to climate impacts contribute to achieving almost all of the other UN Sustainable Development Goals; raising climate ambition is not at odds with economic development and poverty alleviation, but, rather, is essential to achieving those objectives.

The shift to clean energy is also associated with geoeconomic advantages. As the International Energy Agency (IEA) notes in its Net Zero Roadmap (2023a), “momentum is coming not just from the push to meet climate targets but also from the increasingly strong economic case for clean energy, energy security imperatives, and the jobs and industrial opportunities that accompany the new energy economy.”

The outcomes of the United Nations COP28 climate Summit in Dubai provide a strong basis for Brazil to build on, especially the call for all countries to contribute to “tripling renewable energy capacity globally and doubling the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030” and “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science” (UNFCCC 2023a).

There is an urgent need to sharply scale up finance for developing countries to decarbonize their economies; the International Energy Agency estimates that to get on track for net zero emissions by 2050, clean energy investment in the emerging market and developing economies (other than China) needs to increase by a factor of five in the second half of the current decade compared with 2022. Fostering countries’ buy-in to the global energy transition needed to address the climate emergency will require addressing not just the need to scale up finance, but also narrowing the massive disparities between countries on access to the clean technology R&D, supply chains, and markets required to enable an equitable and just energy transition.

Brazil’s G20 Presidency should seek to make progress on several interrelated goals:

Renewable Energy

In their New Delhi Declaration (G20 India 2023), G20 leaders embraced the global goal of tripling renewable energy capacity by 2030, which the IEA’s Net Zero Roadmap shows would make the single biggest contribution to reducing global CO2 emissions by 2030. The challenge now for the G20 is to take the individual and collective action needed to follow through on its support for the 2030 renewable energy expansion goal–particularly in terms of mobilizing much greater sums of public and private finance.

A major objective of Brazil’s G20 Presidency should be to drive much greater renewable energy investment and to address these distributional disparities. This should include securing a tripartite commitment from multilateral development banks (MDBs), the private finance sector, and donor governments to triple the amount of renewable power capacity they finance.

In addition, inadequate investment in grid infrastructure is a major barrier to both faster growth in new renewables capacity and maximizing generation potential from existing renewable capacity. In its report on Electricity Grids and Secure Energy Transitions, the IEA (2023b) notes that achieving countries’ national climate goals requires adding or refurbishing a total of over 80 million kilometers of grids by 2040, the equivalent of the entire existing global grid, and nearly doubling grid investment by 2030 to over US$ 600 billion per year, with emphasis on digitalizing and modernizing distribution grids. Under Brazil’s Presidency, the G20 should develop a roadmap for sharply increasing investments in power grid infrastructure–including support for the expansion and modernization of grid networks; the connection of renewable energy projects; and implementation of smart grid solutions, like storage and demand response.

Energy efficiency

Energy efficiency offers some of the fastest and most cost-effective actions to reduce emissions: it is central to a just and inclusive energy transition. Global collaboration is key to ensuring that countries can reduce energy costs, strengthen energy security, and manage increased pressures on the power grid–including those created by rising demand for cooling.

IEA’s net zero by 2050 scenario (IEA 2023a) requires on average a 4% annual reduction of global primary energy intensity between now and 2030–double the rate achieved in 2022, which itself was nearly double the average rate achieved over the previous five years. The IEA identifies three main levers to achieve this rate of improvements in primary energy intensity, each contributing roughly a third of the gains:

Analysis (IEA 2022) shows that such accelerated action on energy efficiency and related avoided energy demand measures can reduce CO2 emissions by 5 Gt per year by 2030, strengthen energy security by reducing demand for oil and natural gas, contribute to lowering household energy bills by at least US$ 650 billion a year, and support an extra 10 million jobs by 2030 in efficiency-related fields such as in new construction and building retrofits, manufacturing and transport infrastructure.

Brazil’s G20 can build on the New Delhi Leaders’ Summit support for the global goal of doubling energy efficiency and its Voluntary Action Plan for achieving that goal by convening relevant delivery organizations and detailing more concrete action on measures under each of the Plan’s five pillars: the buildings, industry and transport sectors, along with energy efficiency financing and sustainable consumption patterns. This should include giving a strong mandate to the Energy Efficiency Hub[2] to support ongoing global collaboration, and building on the work of Mission Efficiency,[3] which enables developing countries to deliver on their efficiency goals.

As with renewable energy, the G20 should seek a tripartite commitment from MDBs, private finance sector and donor governments to triple investment in energy efficiency finance, as it is needed to get on track for 4% annual improvements in energy intensity by 2030.

The Transition Away from Fossil Fuels

To have any chance of meeting the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 °C temperature increase limitation goal, sharp reductions in the production and use of all fossil fuels over the next decade–including, but not limited to, coal–are essential, en route to a phase-out of all unabated fossil fuels before 2050. As the world’s largest economies, responsible for roughly three-quarters of global oil and gas demand, G20 countries must lead on the global transition to fossil-free energy systems.

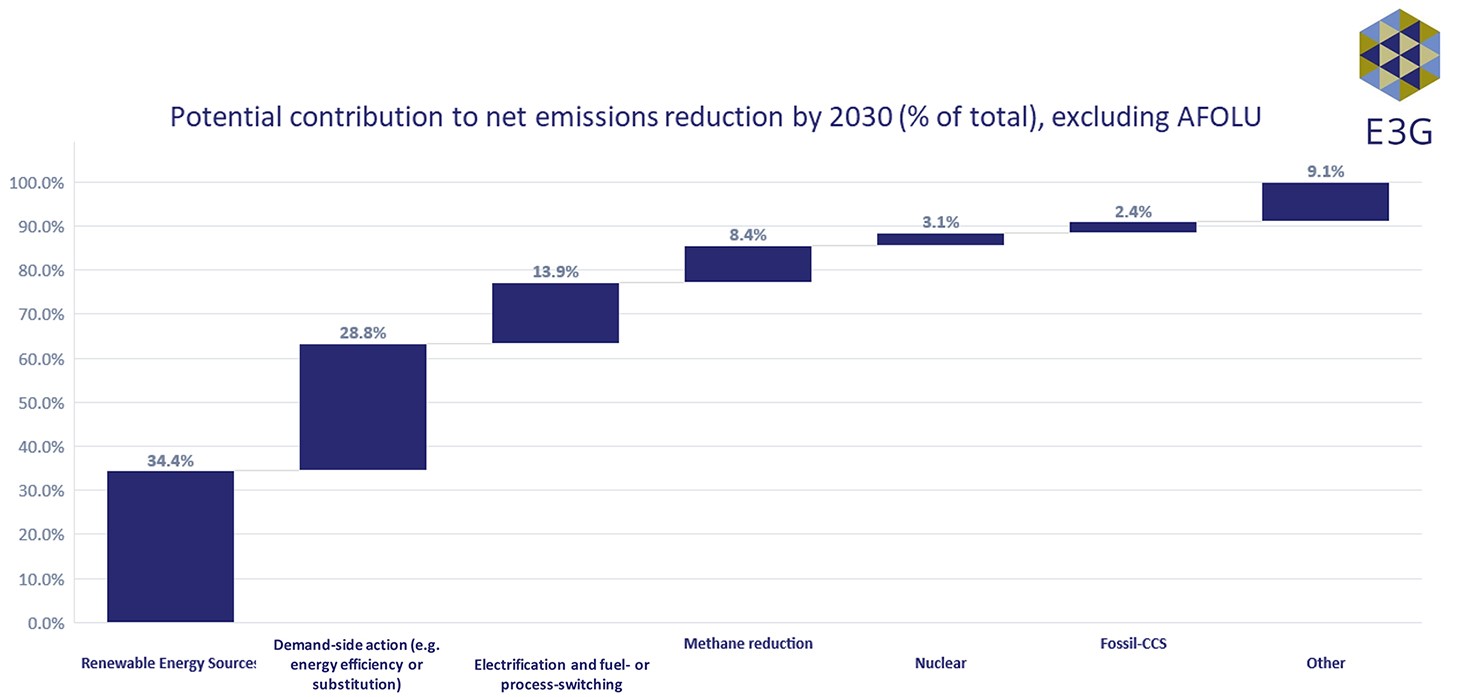

Carbon capture and other abatement technologies may play a role in hard-to-abate sectors over the longer term but, as the graph below makes clear, they will not significantly affect the global emissions trajectory over the next five to ten years and should not be viewed as a substitute for phase-down of fossil fuel production and use.

Figure 1. Potential contribution to net emissions reduction by 2030. Source: E3G calculations based on IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (2022). Notes: AFOLU mitigation options have been excluded. Mitigation options have been grouped in the following categories: 1) Renewable energy sources; 2) Demand-side action such as energy-efficiency or substitution; 3) Electrification and fuel or process switching; 4) Methane reduction; 5) Nuclear energy; 6) Fossil-based carbon capture and storage; and 7) other.

In addition to undermining efforts to meet the Paris Agreement temperature limitation goals, continuing to build new coal plants and expanding oil and gas production endanger true energy security and pose a significant risk of massive levels of stranded assets as the demand for the energy from these investments fails to materialize.

Under Brazil’s Presidency, the G20 should build on its September 2023 Delhi Declaration call for “accelerating efforts towards phasedown of unabated coal power” by including an explicit reference to no new coal in the 2024 Energy Ministerial and Leaders’ Summit communiqués. In addition, as the only country in the Americas with new unabated coal plant projects in the pipeline, Brazil has a unique opportunity to demonstrate its leadership on this front by signalling that it has no need to build new coal plants, because coal cannot compete with cheaper renewables and that it instead intends to utilize its demonstrated high renewable energy resource potential to secure its energy future. As Brazil’s Minister for Finance Fernando Haddad (2023) has stated, decarbonization and diversification from fossil fuels are not a cost, but “an opportunity for creating jobs, raising income and improving the lives of millions of Brazilians.”

The G20 also needs to provide leadership on developing effective and equitable oil and gas transition strategies, both for its own members as well as countries outside the group, including identifying ways to assure provision of the necessary transition finance.

The G20 also needs to provide leadership on developing effective and equitable oil and gas transition strategies, both for its own members as well as countries outside the group, including identifying ways to assure provision of the necessary transition finance. As countries phase down fossil fuels, this transition will create growth potential in some sectors and lead to declining markets and employment in others. Without sufficient planning and timely support–a topic which is addressed in more detail in the economic section below–there are substantial risks of workers, communities, and regions affected by this transition being left behind. In addition to these impacts, gender equality and socioeconomic development must also be addressed as key aspects of a just and inclusive transition. On a positive note, distributed renewables, microgrids, demand-side management, and other small-scale technologies can create substantial employment opportunities and help alleviate energy poverty in underserved communities.

Drawing on the work of the International Labour Organization,[4] the Global Commission on People-Centered Energy Transitions,[5] the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (Kramer 2022) underway in several countries, and other initiatives, the G20 should work to develop an ecosystem of support for just transitions in its own member countries and, more broadly, through establishment of technical, financial, and knowledge networks to help accelerate action. Such multi-stakeholder knowledge networks can help countries better understand the extent of resources needed to implement just transition strategies on issues including skills development, community and local government capacity building, and building social infrastructure.

G20 countries can also provide much-needed leadership in implementation of the UAE Just Transition Work Programme agreed to at COP28 in Dubai (UNFCCC 2023b), which includes the following elements:

Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Since G20 leaders first committed to phase out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies over the medium term at the 2009 Summit in Pittsburgh, G20 communiqués have dutifully repeated this pledge Summit after Summit; however, very little progress has been made. A report published by Bloomberg Philanthropies and Bloomberg New Energy Finance (Bloomberg 2022) estimates that “G-20 member countries provided almost US$ 700 billion in support for coal, oil, gas and fossil-fuel power in 2021–up 16% from the year before and higher than any year since 2014.” An IEA report (IEA 2023c) estimates that global fossil fuel consumption subsidies alone exceeded US$ 1 trillion in 2022.

At their Summit in Delhi in September, G20 Presidency leaders pledged to “increase [their] efforts to implement the commitment made in 2009 in Pittsburgh to phase-out and rationalize, over the medium term, inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption and commit to achieve this objective, while providing targeted support for the poorest and the most vulnerable.” But once again, there was virtually nothing on how to implement this pledge.

By contrast, the policy brief on Financing a Fair Energy Transition through Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform (Sharma et al. 2023) produced by the T20 group as an input to India’s G20 Presidency makes very helpful recommendations on concrete steps G20 countries should take to address this implementation gap:

Brazil should task G20 Finance and Energy Ministers to co-prepare an implementation roadmap on phasing down fossil fuel subsidies, drawing on the T20 group’s policy brief report and other resources, and commit to put it before leaders for approval at their November 2024 Summit.

Managing Competition

Brazil should use its G20 Presidency to help put the world on a more collaborative path to managing competition in clean energy markets. This is a complex and politically charged landscape that includes issues such as supply chain derisking, ensuring the resilience and transparency of critical minerals production and value chains, guidelines for onshoring and “friendshoring” policies, and minimizing carbon leakage through border carbon tariffs.

While there have always been trade and competitiveness issues in the climate and energy space, the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the United States, the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and Green Deal Industrial Plan, and similar initiatives in other countries have elevated issues of competitiveness in cleantech manufacturing, the fair use of green subsidies, and securing access to critical raw materials to the forefront of debate in the G7, G20, IEA, World Trade Organization (WTO), and other multilateral spaces. All of this is taking place in the context of China’s market dominance in many aspects of clean technology and critical minerals production and processing.

There is currently no consensus on how these issues should be discussed and managed in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the WTO, or other multilateral spaces. The G7 leaders laid out a range of proposals in the G7 Clean Energy Economy Action Plan (United States 2023) adopted at their Hiroshima Summit in May 2023. At their Delhi Summit, G20 leaders addressed some of these issues, including pledging to “support reliable, diversified, sustainable and responsible supply chains for energy transitions, including for critical minerals and materials beneficiated at source, semiconductors and technologies”.

A briefing by our E3G colleague Jonny Peters (2023) discusses these issues in more detail and outlines several areas where progress could be made:

Through its G20 Presidency, as well as its leadership of the 2024 Clean Energy Ministerial and Mission Innovation Summits, Brazil should seek to advance multilateral collaboration on these issues.

BUILDING A NEW FINANCIAL REFORM VISION

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of the Bretton Woods Accords, as a variety of voices have repeatedly pointed out (Brookings 2018), the shortcomings of the current global financial system are increasingly evident. At the same time, the G20’s relevance is increasingly being called into question, including from some of its own members; in a recent address to French Ambassadors meeting in Paris, President Macron noted that “we are not seeing that many people knock at the door of the G20” (France 2023). Brazil has a timely opportunity to illustrate its leadership by defining a new global financial reform vision for climate and development.

This new global financial consensus rests on two key efforts:

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs)

Reforming the global financial system’s institutions starts with bigger and better multilateral development banks (Scull 2023), and, while progress has been achieved in 2023, much remains to be done. This issue was identified by President Lula as one requiring action in the speech he gave during the G20 Meeting of Sherpas, deputy ministers of Finance and Central Bank Representatives in Brasilia on December 13, 2023.

The first priority should be to sustain efforts started in 2021 under the Italian G20 Presidency to implement ambitious changes to MDBs’ capital adequacy framework (CAF) and deploy their full financing potential. This means progressing with measures identified by the G20 Roadmap for implementing the recommendations of the G20 Independent Review of the CAF endorsed by G20 Leaders. But ambition on this agenda can be further increased, notably by more explicitly incorporating recommendations formulated this year by a G20 Independent Expert Review Group in the Roadmap–as so far these recommendations have been merely “noted” and “examined” by G20 Finance Ministers. Another ambitious path forward could be to expand this agenda to include regional development banks.

The second priority should be to increase MDBs’ financial firepower, i.e., their capitalization levels. Achieving this across the board will take years, but Brazil should seize the window of opportunity opened up last October by G20 Finance Ministers–the communiqué they published after their last meeting under the Indian Presidency mentioned for the first time the possibility of capital increases for MDBs–and build on it. Brazil could focus on political bandwidth for the year ahead by discussing this matter on a bilateral basis with key shareholders of G7 countries (especially the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France) in advance of key G20 meetings, identifying urgent targeted increases first (such as the replenishment of the World Bank’s International Development Association).

The third priority should be to deepen discussion on the MDB system’s governance: Are their mandates adequate? How do they or should they work together (Reyes 2023)? What about other institutions, such as public development banks or regional development banks? In an address in Marrakech, an updated mission for the World Bank (2023) was recently announced by its newly appointed president, Ajay Banga: “to create a world free of poverty, on a liveable planet.” The MDB governance conversation should be broadened beyond the World Bank, and systematized.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) Reform

Reforming the global financial system’s institutions also requires deepening reform of the IMF. Similarly to MDBs, there are various issues at play here, and the first is financial. The recent approval by the IMF Board of a proposal to increase the Fund’s quotas (IMF 2023) is good news, in troubled times, for the global financial safety net. But Brazil could also encourage early G20 discussions on the capacity of the IMF to deliver increased financial support where needed through a new US$ 650 billion issuance of Special Drawing Rights in 2026, and continue to push the envelope to durably address fiscal space issues–in particular by examining the need and potential impacts of incorporating climate change into the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Analysis (Maldonado & Gallagher 2022).

The recent approval by the IMF Board of a proposal to increase the Fund’s quotas (IMF 2023) is good news, in troubled times, for the global financial safety net. But Brazil could also encourage early G20 discussions on the capacity of the IMF to deliver increased financial support where needed…

The second issue is methodological. The IMF has a wide range of policy tools at its disposal; but despite Kristalina Georgieva’s determination to mainstream climate across the IMF’s toolbox and hire numerous climate economists to join the ranks of the institution, much remains to be done. Brazil should push for increased transparency and consistency of these methodological approaches, considering their immediate financial impact on developing countries.

The third issue is a governance one. President Ruto of Kenya pointed out (Bryan & Mooney 2023) the built-in limitations to what the IMF could achieve, based on its existing shareholder structure. The IMF Board recently approved a call (IMF 2023) to develop possible approaches to realigning the Fund’s quotas by June 2025. This is a significant step forward, and Brazil should seize this opportunity to shape the terms of this debate and build strong G20 support and proposals–in close coordination with South Africa (which will hold the G20 2025 Presidency).

Transforming the Financial System’s Inner Workings

Brazil should further raise the stakes in 2024 by integrating more squarely, in the G20’s narrative, agenda, and outcomes, the need to also transform the financial system’s terms of operation–its norms, rules and legal frameworks–in order to strengthen what the IMF refers to as the “climate information architecture” (Ferreira et al 2021).

The 2006 Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change (Stern 2006) marked a pivotal moment in the conceptual thinking about climate change. While various factors (e.g. historical, geopolitical, political or social) can explain the problem, Nicholas Stern offered a simple and powerful explanation of climate change in economic terms. Indeed, he described climate change as a prime example of a “market failure” (i.e., the inefficient distribution of goods and services in a free, and supposedly efficient, market). In this specific case of market failure, the inefficiency pertains to greenhouse gas emissions–the unpriced yet negative by-product, or “externality”, of valuable economic activities. This powerful explanation proposes a simple path to unravel the range of complex problems posed by climate change (including risks to financial stability, market integrity, consumer protection, social resilience): reintegrate climate-related and nature-related information in our economic and financial systems.

Transition Plans

Transition plans are a key emerging norm that holds the potential to deeply transform the global financial system’s inner workings and secure its resilience to climate change, as well as that of the social contract within and across countries. They were recognized as an important tool in 2023 by various international forums–from the G7 to the IMF to the UN, with many other international standard-setters creating working groups on the topic. Under Brazil’s stewardship the G20, especially through its Sustainable Finance Working Group and the newly created Global Mobilization against Climate Change, could add significant value to this conversation by:

It is certain that transition plans are a politically sensitive topic. Designing and implementing them involve making choices with significant potential consequences, whether at the national level or for one’s business. In addition, broadly speaking, developing countries have justified concerns about the way new, common financial standards may impact their ability to attract capital flows.

Brazil itself needs to balance its significant domestic ambition on sustainable finance issues with its most pressing domestic development issue: hunger, and the pressures this creates on the agricultural sector’s own transition considerations.

These challenges, however, are precisely the reason why Brazil is best placed to carry forward this conversation. Brazil itself needs to balance its significant domestic ambition on sustainable finance issues with its most pressing domestic development issue: hunger, and the pressures this creates on the agricultural sector’s own transition considerations. Having also favored a “common but differentiated responsibility” approach in other policy areas, Brazil is uniquely well suited to shepherd this approach to transition plans specifically and new global financial norms more broadly. Bringing these conversations to the table would be the most impactful way for Brazil to demonstrate the political courage and cutting-edge leadership that is expected of President Lula’s administration.

International Investment Regime

Brazil could further demonstrate cutting-edge vision by including in its G20 agenda the matter of ISDS, a critical legal framework that governs foreign investments. The current international investment regime is made up of more than 2,500 investment treaties and trade agreements with investment provisions. The central pillar of the regime is an investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism, which allows foreign investors to bring claims against host governments if they consider that policy measures have undermined their business interests. The ISDS mechanism is designed to give security to foreign investors and therefore has been believed to attract foreign investment. The 1990s witnessed a surge in the number of newly signed investment treaties with ISDS.

However, ISDS then became controversial for decades as it puts corporate interests above other objectives and values, such as human rights, climate and environment. Notably, fossil fuel investors have become the most frequent users of the system. With the urgency of the climate crisis, the need to stop the current investment treaty regime from hindering climate action has attracted much attention recently, resulting in several European countries exiting from the Energy Charter Treaty–the most invoked investment treaty in the world.

In the IEA’s climate-driven scenarios (2021), over 70% of clean energy investment in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) should come from the private sector by 2030. For most EMDEs, the role of international private finance is particularly important, but the current level of participation is well below its potential. However, investment treaties interrupt the necessary scaling up of cross-border investments in clean energy because they protect and therefore over-induce fossil investments. Just as with other existing norms such as the ones inherited from the Bretton Woods accord, the international investment regime as it stands no longer works in the fight against climate change. Sparked by the Energy Charter Treaty, there are some multilateral discussions at a technical level regarding how to fix the current regime. Addressing this at G20 would provide a political momentum to advance the agenda.

The starting point would be for G20 countries to recognize ISDS as a barrier to climate action and to commit to identifying ways to better align investment treaties with climate goals. Although recent G20 energy ministerial or finance ministerial documents have captured the importance of increasing international private finance, they have never shed a light on investment treaties and ISDS. Brazil could also lead the positive agenda of how to promote and facilitate investments that support climate action and guide discussions to adopt a set of guidelines, where it could disseminate its alternative treaty model and its practices among G20 countries.

Here too, Brazil is well positioned to drive this timely agenda. It is one of the most progressive countries in its approach to investment treaties and has never ratified any investment treaty with ISDS. As one of the largest FDI recipients but also a leading donor of renewable energy investment, Brazil can bridge interests of both capital exporters and capital importers. Championing the agenda of reshaping investment governance that works for climate would signal Brazil’s commitment to clean energy investment. It would also be a good opportunity to show Brazil’s leadership on shaping global rules in line with the Paris Agreement. With South Africa being another progressive State in the investment policy space, this agenda could continue in 2025 and further strengthen South-South leadership.

CLOSING REMARKS

As the “premier forum for international economic cooperation,” the Brazilian G20 should deliver a clear and ambitious political consensus to respond to existing challenges, anticipate forthcoming ones, and enable thriving societies and economies.

The G20 is an economic forum with strong potential to steer the world in the right direction and deliver ambitious and impactful outcomes, but a lack of focus and unity of purpose has too often stood in the way of achieving that objective. President Lula has already stated the highest level of ambition to achieve global goals and tackle wicked problems. As the “premier forum for international economic cooperation,” the Brazilian G20 should deliver a clear and ambitious political consensus to respond to existing challenges, anticipate forthcoming ones, and enable thriving societies and economies. This includes framing increased climate ambition in relation to achieving other sustainable development goals, including food security, health, good jobs and other priorities. More broadly, landing major progress at the G20 on the clean energy transition and a new financial reform vision would reinvigorate a climate of trust and cooperation.

Notes

[1]See the official G20 Brazil website: https://www.g20.org/en/.

[2]See: https://energyefficiencyhub.org/.

[3]See: https://missionefficiency.org/.

[4]See: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/publications/just-transition-pb/lang--en/index.htm.

[5]See: https://www.iea.org/programmes/our-inclusive-energy-future.

Berman, Noah & Sabine Baumgartner. 2023. “The Weather of Summer 2023 Was the Most Extreme Yet.” Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). CFR.org, September 18, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/article/weather-summer-2023-was-most-extreme-yet.

Bloomberg. 2022. “2021 Support For Fossil Fuels by G-20 Nations Reached Highest Level Since 2014.” Bloomberg.org, November 1, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.org/press/2021-support-for-fossil-fuels-by-g-20-nations-reached-highest-level-since-2014/.

Brazil. 2023a. “Speech by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva during the Summit for a New Global Financial Pact, in France.” Planalto. Gov.br, Jun 23, 2023. https://www.gov.br/planalto/en/follow-the-government/speeches/speech-by-president-luiz-inacio-lula-da-silva-during-the-summit-for-a-new-global-financial-pact-in-france.

Brazil. 2023b. “At the UN General Assembly, Brazil’s Lula Calls for Global Union against Inequality, Hunger and Climate Change.” Planalto. Gov.br, Sep 19, 2023. https://www.gov.br/planalto/en/latest-news/at-the-un-general-assembly-brazil2019s-lula-calls-for-global-union-against-inequality-hunger-and-climate-change.

Brazil. 2023c. “Nota Técnica PRODES Amazônia 2023.” Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE). Gov.br, November 10, 2023. https://www.gov.br/inpe/pt-br/assuntos/ultimas-noticias/estimativa-de-desmatamento-na-amazonia-legal-para-2023-e-de-9-001-km2.

Brookings. 2018. “How to Reform the Global Monetary System: A Pathway to Action.” Brookings.edu, April 17, 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/events/how-to-reform-the-global-monetary-system-a-pathway-to-action/.

Bryan, Kenza & Attracta Mooney. 2023. “Kenya’s William Ruto: ‘We are not Running away from our Debt’.” Financial Times, August 10, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/214dbc09-c8ad-4645-b943-8a182a08bd46.

Ferreira, Caio, David L. Rozumek, Ranjit Singh, Felix Suntheim. 2021. “Strengthening the Climate Information Architecture.” Staff Climate Note No 2021/003. International Monetary Fund (IMF). IMF.org, September 8, 2021. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/staff-climate-notes/Issues/2021/09/01/Strengthening-the-Climate-Information-Architecture-462887.

France. 2023. “Conférence des Ambassadrices et des Ambassadeurs: le discours du Président Emmanuel Macron.” Elysee.fr, August 28, 2023. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2023/08/28/conference-des-ambassadrices-et-des-ambassadeurs-le-discours-du-president-emmanuel-macron.

G20 India. 2023. G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration. New Delhi, India, 9-10 September 2023. https://www.mea.gov.in/Images/CPV/G20-New-Delhi-Leaders-Declaration.pdf.

Gaspar, Vitor, Marcos Poplawski-Ribeiro, Jiae Yoo. 2023. “Global Debt is Returning to its Rising Trend.” International Monetary Fund (IMF). IMF Blog. IMF.org, September 13, 2023. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/09/13/global-debt-is-returning-to-its-rising-trend.

Haddad, Fernando. 2023. “Brazil’s Plans to Transform our Green Economy.” Financial Times, September 18, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/fda15a48-b6ab-44fe-9bc0-1127feedaa80?accessToken=zwAGBchIV59gkdP9oVpItqtE_tObwBEn_u2qgA.MEUCIQCXCLP6-8zEdbK539O9Ic3_evIrzYEs2a9lmyRCo1QFzQIgAyEXa6DYeSnu6YQzh-OwHwHKnuouZ1QjJrQwJcbFS9o&sharetype=gift&token=e973e20f-e452-402f-aaaf-716559a0683b.

IEA. 2021. “Financing Clean Energy Transitions in Emerging and Developing Economies.” International Energy Agency. IEA.org, June 2021. https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economies.

IEA. 2022. 7th Annual Global Conference on Energy Efficiency. International Energy Agency. IEA: Paris. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/6ed712b4-32a3-4934-9050-d97a83a45a80/Thevalueofurgentaction-7thAnnualGlobalConferenceonEnergyEfficiency.pdf.

IEA. 2023a. Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach. International Energy Agency. IEA: Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach.

IEA. 2023b. Electricity Grids and Secure Energy Transitions. International Energy Agency. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ea2ff609-8180-4312-8de9-494bcf21696d/ElectricityGridsandSecureEnergyTransitions.pdf.

IEA. 2023c. Fossil Fuels Consumption Subsidies 2022. IEA: Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/fossil-fuels-consumption-subsidies-2022.

IMF. 2023. “IMF Executive Board Approves a Proposal to Increase IMF Quotas.” IMF.org, November 7, 2023. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/11/07/pr23383-imf-executive-board-approves-a-proposal-to-increase-imf-quotas.

IRENA & CPI. 2023. Global Landscape of Renewable Energy Finance, 2023. Report. International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Abu Dhabi. https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Feb/Global-landscape-of-renewable-energy-finance-2023.

Kramer, Katherine. 2022. Making the Leap. The need for Just Energy Transition Partnerships to Support Leapfrogging Fossil Gas to a Clean Renewable Energy Future. Policy Brief. International Institute for Sustainable Development. IISD.org, November 2022. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2022-11/just-energy-transition-partnerships.pdf.

Maldonado, Franco & Kevin P. Gallagher. 2022. “Climate Change and IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis.” Boston University Global Development Policy (GDP). Bu.edu, February 10, 2022. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2022/02/10/climate-change-and-imf-debt-sustainability-analysis/.

OECD. 2023. Towards Orderly Green Transition: Investment Requirements and Managing Risks to Capital Flows. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). https://www.oecd.org/investment/investment-policy/towards-orderly-greentransition.pdf.

Peters, Jonny. 2023. “The Coalition of Trade Ministers on Climate. Turning Commitments into Action.” Briefing Paper. E3G. E3G.org, September 2023. https://www.e3g.org/wp-content/uploads/E3G-Briefing-Coalition-of-Trade-Ministers-on-Climate.pdf.

Reyes, Laura Sabogal. 2023. “Brazil and its Upcoming G20 Presidency: Empowering Emerging Giants.” E3G Blog. E3G.org, October 16, 2023. https://www.e3g.org/news/brazil-and-its-upcoming-g20-presidency-empowering-emerging-giants/.

Scull, Danny. 2023. “Bigger, Better, Faster? A Year of Reforming the World Bank.” E3G Blog. E3G.org, October 2, 2023. https://www.e3g.org/news/bigger-better-faster-a-year-of-reforming-the-world-bank/.

Sharma, Shruti et al. 2023. “Financing a Fair Energy Transition through Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform.” T20 Policy Brief, July 2023. https://t20ind.org/research/financing-a-fair-energy-transition-through-fossil-fuel-subsidy-reform/.

Stern, Nicholas. 2006. “The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review.” London School of Economics and Political Science. LSE.ac.uk, on 30 October, 2006. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/the-economics-of-climate-change-the-stern-review/.

United Nations Environment Programme. 2023. “Broken Record: Emissions Gap Report 2023”. https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2023.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2023a. Advance Unedited Version of Decision -/CMA.5 on the Outcome of the First Global Stocktake. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma5_auv_4_gst.pdf.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2023b. Advance Unedited Version of Decision -/CMA.5 on the UAE Just Transition Work Programme. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma5_auv_5_JTWP.pdf.

United States. 2023. “G7 Clean Energy Economy Action Plan.” The White House. Whitehouse.gov, May 20, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/20/g7-clean-energy-economy-action-plan/.

Whiting, Kate & HyoJin Park. 2023. “This is why 'Polycrisis' is a Useful Way of Looking at the World Right Now.” World Economic Forum. Weforum.org, Mar 7, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/polycrisis-adam-tooze-historian-explains/.

World Bank. 2023. “The World Bank's Bold New Vision.” Worldbank.org, October 13, 2023. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2023/10/13/world-bank-president-on-ending-poverty-on-a-livable-planet.

Submitted: November 21, 2023

Accepted for publication: December 18, 2023

Copyright © 2023 CEBRI-Journal. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original article is properly cited.